. . . This page is currently a work in progress . . .

Moise Allatini

The Angel of Salonica

Moïse [Moses] Allatini (1809–1882) was an entrepreneur and philanthropist in Salonica —who also happens to be my great great grandfather.

Moïse Allatini is lauded as “The Angel of Salonica” by Jews and Muslims alike for his philanthropic and social work, significantly the education of women as a means to improve society as a whole — something that particularly intrigues me, given my own commitment to the cause via my project Eyeing Medusa. This, in fact, is why I decided to paint him.

About Moïse Allatini — “The angel of salonica”

Moïse Allatini came from a long line of Sephardic Jews — Rabbis and doctors, chased out of Spain in the 15th century, by the Alhambra Decree of 1492 — who nevertheless prospered in Italy and Salonica.

Night Scene from the Inquisition, Francisco de Goya, 1810, National Museum of Art

The Jews of Salonica in the Ottoman Era had a long tradition of involvement in trades connected with the sea. Until 1912 all port operations in Thessaloniki were in Jewish hands.

photo: http://www.holocausteducenter.gr/mt-content/uploads/2016/05/1m.jpg

Fratelli Allatini, as the family business became known, were also ship-owners. This intrigues me.

"Göke" (1495) was the flagship of Kemal Reis Contemporary miniature from the Ottoman period, Topkapı Palace Library, Istanbul, image public domain

In ancient times encaustic painting was devised as a method for painting ships because it stood up to sun, salt and winds. The word «encaustic» derives from a Greek work «enkaustikos» meaning burnt in. Encaustic painting involves melting wax, damar crystals and pigment to create the encaustic medium. This is then melted, painted on while hot, and then fused to the surface.

Encaustic painting originated with the Greek artists as early as 5th century BC. It’s fun to imagine that the painting technique that so enchants me today, might have been used on my ancestors’ ships!

A story . . .

In 2007 I received a letter from a researcher, Al Gregoriou, compiling a history of Salonica, in which he mentioned how well regarded Moïse Allatini had been in his time and how he was still remembered to this day.

Apparently, during Moise’s funeral all the bells of the orthodox churches rang, the Muslims joined in mourning, the flags of the consular pavilions were lowered to half-mast and most of the shops in the city lowered their curtains. His family home had become the town Prefecture.

Villa Allatini

How had this escaped mention in my family?

My father Desmond Scott was not surprised. He seemed more amused than anything else, but showed little interest in pursuing the matter further . . .

Fast forward to 2022 when I began researching background information for the subject of my painting Themis — Impressions of Katerina Sakellaropoulou — part of my project Eyeing Medusa.

It turns out that Katerina Sakellaropolou was born in Thessaloniki. Since that rang a bell, I started exploring the history of Thessaloniki.

The more I dug, the more I discovered about Moïse Allatini — my great great grandfather.

Themis — Impressions of Katerina Sakellaropoulou, Amanta Scott, encaustic on canvas on birch panel, 36x36

Moise Allatini (1809-1882)

image © Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki

“Moise Allatini became a legend of Thessaloniki’s modern history not only for his entrepreneurial achievements but also for his social activities.

The modern school system and charitable organizations in Thessaloniki were closely linked to Moise Allatini and Fratelli Allatini, as the family business was known. ”

“[Moïse Allatini] was the third richest man in all the Ottoman Empire, after the Camondo Family (Constantinople or Istanbul, Turkey), and Modiano Family (Salonica, Greece).”

Letter from Dr. Allatini to P. Beaton in 1856

“The Israelites of Salonika are, for the most part, of Spanish descent; they left the land of their birth in the year 1492, the victims of the cruel edict, which proclaimed their expulsion, in the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella. Most of them retired to the East; a small number of them settled at Salonika. Sultan Bajazit, the son of Mehemet, who was reigning at this time, promised them full freedom of worship. Moreover, Jewish families had already taken up their abode at Salonika, in consequence of the security which they enjoyed.

The surest proof of their Spanish descent is the general use of the Spanish language amongst them, which is spoken with an accent peculiar to the Jews, and very much corrupted, as no study is bestowed upon it. Their mode of writing it is still more corrupt, so that it affords them little assistance in commercial affairs.

The Jewish youth are not accustomed to any kind of study; the most that the boys learn is Hebrew, but it also is acquired with a very bad accent, and in such an antiquated way, that most of them learn little else than the mechanical reading of the daily prayers. They only learn as much arithmetic as is indispensably necessary for the management of their affairs. It is an extremely rare case for a Jew to think of reading a book, unless he be an aspirant to the office of Rabbi. It is all the more to be regretted, that the instruction of the Jewish youth is confined within such narrow limits, not only here, but throughout the whole of the East, inasmuch as the Jews themselves make no effort to master the Turkish language. Thus, they are never in a position to enter into direct communication with the great mass of the population, and are always regarded, in the land of their birth, as a race that is merely tolerated and despised.

Scarcely has the young Israelite passed from childhood to youth, than he rushes into the whirlpool of public life. Most of them devote themselves to commerce. Very few of them are mechanics, and the few, that have learned trades, are very bad workmen. Many lounge about idly in the streets, trusting to accident for support, and thus soon lapse into a state of mendicity.

When the Jew is endowed with more than ordinary intelligence, he soon contrives, notwithstanding the defects in his early training, to acquire wealth here by his activity in business. It is a singular circumstance among the trading classes in the East, no matter to what religion they may belong, that fortunes are never transmitted to families by inheritance.

The cause of this deplorable state of things is to be found in the small amount of security which is enjoyed under the Turkish law, and in the despotic government. Individual families are plundered by the great; and communities by the pashas. Repeated outbreaks of pestilence, and frequent fires, augment the misery of the poor inhabitants. Always when ready to put forth their energies again, they are visited by some fresh disaster.

The charter of the Gül Hane has tended in some measure to ameliorate this deplorable state of affairs; already efforts are made in some Jewish families to secure their property to their future heirs. Still, these cases are so very exceptional, that the majority, who belong to the necessitous classes, live in the same miserable condition as before.

Another circumstance, and perhaps the principal cause why the Levantine Jews are never able to make any certain provision for their children, is to be found in the fact that their children marry at a very early age. Young lads marry at 17 or 18, girls at 13 or 14 years of age. In this way, families are very numerous, and one can easily conceive in what a miserable condition a man often is at his thirtieth year, who must not only support his own family, some 10 or 12 in number, but receive into his house his sons who are already married, but not yet in a position to provide for their wives and children.

Oppressed by such heavy cares, the Jewish merchant never enters into any new enterprise, or embarks on a journey; he labours merely for the daily sum, that suffices for the wants of his numerous family.

The women are unaccustomed to any kind of intercourse with society, and to every species of labor. Married young, they are too soon overburdened with domestic cares, worn out, often prematurely old and sick. Of late years, women of the poorer class may be seen employed in weaving silk.

The laws of the Turkish Empire secure to its Jewish subjects the possession of immovable property, and it may be said with certainty, that every Jewish family is the proprietor of their own house. Yet their dwellings are so crowded together, that their health suffers in consequence, and they have always suffered most during the prevalence of any epidemic.

There are no husbandmen or gardeners amongst them; the reason of this may be, that the Israelites always feel the necessity of living close together, and of not being dispersed over the country.

A solitary village in our province contains the remains of a synagogue and of a Jewish burying ground, though for years no Jew has been resident in this village. A chronicle relates that the Jews, terrified by the great oppression to which they were subjected, gradually removed to Salonika. A few years ago, a Jew, who possessed landed property, was not in a position to superintend or to manage it. We hope that it will now be otherwise, but we regard the practice of agriculture by Jews, as difficult, if not impossible.

The Israelites of Salonika use the Spanish ritual in their devotions; they have twenty-seven synagogues, the largest of which bears the name of Talmud Tora. But it must be observed, that there are still two synagogues, which use the Italian and German rituals, and, judging by the date of their erection, these are the oldest.

There are no Karaites, or other sects, but many Krypto Hebrews, followers of Sabatai Zewi; they are named Mimim in the land of “Mamini”, because they are professedly attached to Mohammedanism. They form a peculiar caste, and are equally distinct from the Jews and the Turks. They practice openly the rites of Islamism; still, they themselves confess that they form a peculiar sect. The Government does not recognize them as such, and treats them as Mussulmans, and admits them to the enjoyment of the same rights.

This sect again is divided into three different communities, which mutually hate and despise one another, in a manner which it is difficult to account for. They only intermarry with one another, and each sect with its own members; they never contract marriages with real Mohammedans.

The misery of early marriages, to which we have already alluded, is most clearly perceptible among them; the race is visibly dying out; scrofula, rickets, and all kinds of hereditary diseases are prevalent amongst them. Two of these sects are distinguished by their names; they call themselves Cavaglieros and Cognos, probably after their founders. It is known that one of these two sects continues to read the Jewish books, but professes great respect for the book of Zoar. I cannot say much about the peculiar customs of the Minim, because they strictly conceal their religious mysteries, and, from fear that they may be surprised into the disclosure of any of them, they abstain from wine to such an extent, that they never drink water from a vessel, when they suspect that it may possibly have contained some spirituous liquor.

They never answer any question regarding their circumstances or forms of worship. It is asserted that a Min, who, some years ago, had betrayed one of their secrets, was put to death by his sect.

Besides the Jews, who are Turkish subjects, there are many from other lands, who have placed themselves under the protection of their different consuls. The greater number of these foreign Jews is known here by the name of Franks. They differ little in their manners and customs from those born in the country, and only a few families send their children to France or Italy to be educated. There are tutors in some families, but such cases are extremely rare.

All the leading members of the community have a vote in the election of the Rabbis. The oldest and most learned Rabbi, who has given proofs of his religious knowledge, is usually elected. A preference is usually shown for those, whose forefathers were Rabbis of distinction. When several, from their knowledge and influence, have an equal claim, four or five Head Rabbis are often chosen, the oldest of whom has the preeminence, while the duties of the office are transferred to the one best qualified. The community asks and receives in the name of the eldest, through the Head Rabbi at Constantinople, the right of investiture from the Turkish Porte, in virtue of which the newly elected Rabbi is recognized as spiritual head of the Israelites at Salonika.

His jurisdiction only extends to the Jews of this city and to the communities of Seres Beolila [Bitola] and Donau [?] Scopia, and, more recently, Larissa, Tricala, and Janina, have been included in it. The authority of the Head Rabbi is very extensive; he has the right to pronounce sentence of punishment on both the soul and the body, if he has given previous intimation to the authorities, who carry it into execution. The Head Rabbi receives no fees from the community; his position, therefore, is not very splendid, so that he cannot support the external dignity of his office. He has no particular voice in the government of the community, but, in compensation, he presides over it and over all the rabbinical courts of justice, and all difficult and intricate questions must be submitted to him.

There are four Rabbinical courts:—

-One for watching over and protecting the interests of widows and orphans.

-One for deciding differences in civil and commercial affairs.

-One for the management of immovable property; this institution is perfectly useless, as the authorities alone draw up the title-deeds, and in cases of dispute the decisions of the Rabbis have no effect.

-Lastly, one for religious questions and matters of conscience.

Besides these four institutions, there are others of less importance, which attend to the ordinances of religion; disputes between husband and wife; the inspection of meat exposed for sale, &c. Besides these ecclesiastical courts, there is another, composed of five presidents, who are chosen annually, and who transact all kinds of business with the Government, and give counsel on local and general affairs, under the presidency of the Head Rabbi.

There is no book of taxes kept by the Government of the community. The one which is submitted to the Turkish Government is not correct, as the Jews, from their dread of oppression, always conceal their numbers. It cannot therefore be stated with certainty whether there are more or less than 3,500 families, with 16,000 Jewish subjects of Turkey, in Salonika. They have hitherto been looked upon by the Ottoman Government as merely a mass of men from whom a certain tax had to be raised, and for the payment of which the Israelitish community was held responsible.

Every three years, a committee of four or five men is chosen, whose duty it is to regulate the taxes to be levied on the members of the Jewish community, according to their means. If the tax is too high for the means of a family, the complainant must confirm this by an oath; such a case, however, rarely occurs.

The community levies a tax chiefly on articles of consumption, as meat, wine, and other comestibles; it derives also certain fees from marriages, births, deaths, and legacies. While it takes advantage of these, it tries to levy direct taxes on individuals as little as possible, and the collection of these is always very unpopular. The poll-tax was formerly levied by the Government, which, in return, paid for the support of the Rabbis, of the different office-bearers, and of the poor and sick. This regulation was a very good one, inasmuch as the office-bearers and employees of the community were more independent of it, and treated with greater respect. Still there resulted an immense expenditure, from want of order, and ill-kept books, which could neither be checked nor punished. Since the alteration in the system of expenditure and the abolition of the former regulation, certain individuals represent the mass on which the taxes are leviable.

There is a fixed tax on immovable property; every proprietor, whether he be a Greek, a Turk, or a Jew, escapes as a landed proprietor, while the Jewish community is responsible to the Government, for the present, and for all future time. This responsibility rests upon a previous liability, which amounted to 50,000 francs. When the system of taxes was changed, the community tried to get this ancient liability examined afresh, and thus to ameliorate their own condition; but this attempt met with little favour, and the community now owes a sum of 100,000 francs to some private individuals.

The feeling of benevolence is active enough. A great deal is done for the sick and the poor, but yet, even in this, there is a great want of system. The distribution of alms is very unjust, and idleness often meets with a larger amount of support than real helpless poverty.

With regard to learned men at Salonika, without alluding to those of past celebrity, I must mention in terms of laudation Rabbi Ascher Covo, who is now [still] alive. He is a man of irreproachable character, and his biblical and talmudical knowledge is at once profound and extensive. He is surrounded with prudent and learned men, is anxious to introduce new regulations consistent with the requirements of the community, and is supported in his endeavours by another worthy Rabbi, Mr. Abraham Gattegno, who holds the office of president, in the court for widows and orphans.

There is not a single man who cultivates literature or poetry, and it is matter of regret that we possess neither historical works nor chronicles. It is affirmed that there are many documents, as well as manuscripts, scattered about, from which more minute information might be derived; but I have never seen any of them. After this statement of the circumstances of the Jews at Salonika, it only remains for me to answer a few of your questions:—

Whether the Jews alone have fallen into such moral degradation, and what difference is perceptible between them and the Turkish and Greek communities?

What are the causes that have brought about and still keep them in their present deplorable condition?

What steps are necessary to effect an improvement?

In general, the Turk has not advanced with the spirit of the times more than the Jew. I speak here of the whole nation, and not of isolated individuals; so that, so far as concerns moral progress, there is no perceptible difference between them. A short time ago, the Greek raja was in the same deplorable condition; but the Greek revolution had a beneficial effect on the Christians of the Turkish Empire. The proximity of Greece is of the greatest advantage to the young men desirous of learning, who are sent there for their education. The Greeks, scattered over the whole of Europe, have found a central point of union, and support their brethren, who are subject to the Turkish Government. They send money for the erection of schools; they encourage and aid their co-religionists, and, within twenty years, can point to splendid results. The Greeks, born in this country, travel, acquire knowledge in foreign lands, and then introduce improvements at home, erect schools, and thus make progress in civilization. In point of intellect, the Greek is superior both to the Jew and the Turk.

The chief cause of the miserable condition of the Jews is to be found in the hostile spirit of the prevalent religion, and the hatred of the Government. There has been a change in this feeling of late years. The recent regulations have been conceived in a generous and liberal spirit; still, there will be great negligence in carrying them into execution, as events already prove. The Jew stands isolated and unsupported; his existence is confined to the circle of his own family; he does not feel the necessity of learning anything, while, if he remains ignorant, he is surrounded on all sides with difficulties which discourage him.

Besides these causes, I find that the Jews, chiefly Franks, who find their way here, possess only a superficial civilization. They propagate among the masses the belief, that schools, instruction, reforms, are a desecration of religion, and thus there has arisen, if not a feeling of hatred against western improvements, at least a feeling of distrust, and a great amount of indifference. The improved circumstances of the Jews of Salonika within a recent date, as well as their extensive business, have induced the necessity of imparting a higher education to the young men. Although the parents are very indifferent about the education of their children, and very parsimonious in meeting the necessary expense, the advantages of an improved education are already evident. The children are far in advance of their parents in the transaction of business, and in their knowledge of religion. They show that men may cast aside superstitious customs without becoming atheists. They are treated with consideration, and even the Rabbis are not unkindly disposed to them.

The line of demarcation, which formerly separated the native from the foreign Jews, has grown less clearly defined of late years, and though the foreign Jews are not obliged to contribute to the expenses of the community, they have themselves set aside a sum for the relief of the poor.

The Head Rabbi of Constantinople, encouraged by the presence of Baron Rothschild, published rules for schools, and improvements for the metropolis and the provinces. Constantinople has already a French Israelitish school, which owes its existence to Mr. Albert Cohen, and meets all the requirements of that great city.

The Imperial Hat Humayoun has bestowed equal civil rights on all religious sects, and good results are already evident. The desire for schools is becoming perceptible, the system of instruction in Hebrew has been much improved, and the youth will soon be instructed in the Turkish as well as the French language. Other cities in the empire will, I hope, not remain behind; and thus we may indulge the expectation that we have made a great step in advance.

Still, it is necessary to strengthen and encourage the desire of knowledge which has been thus fortunately excited. What a splendid example has been presented by the families Montefiore and Rothschild; what activity and self-denial by Mr. Albert Cohen and you, in furnishing your contribution in the name of Madam Herz Lämel! How anxious Mr. Phillipson was to stir up the Jews to benevolent undertakings for the benefit of the holy city by means of his journal! It is not the fault of the unfortunate Israelites of the East, as we have here shown, that they have fallen so low.

To enable them to work their way out of their present miserable state of degradation, they require material and moral support, so that this depressed race may no longer be heard saying; “We cannot, because we have not the means.” I do not mean that they must be assisted with alms; moral support is much more necessary; contributions for the general good, instead of benefits conferred on particular individuals.

It were desirable, also, that travellers of talent and energy should direct their attention to us—examine into our circumstances—encourage the Rabbis, and give an impulse to the population.

In reply to your questions, I have described the sufferings of my brethren, and pointed out the sources from which assistance may flow to them. Perhaps you may succeed some day in bringing about a reform among our co-religionists. I authorize and request you to publish my report in the journals, or in any other way which you may deem most suitable for attaining the object which you have in view.”

family history

Today the Allatini name is famous for the Allatini Family, particularly Moïse Allatini.

Following the family tradition Moïse Allatini studied medicine in Florence and Pisa, earning a doctorate in medicine from University of Pisa, Italy. However, he never practiced his profession; his father’s death in 1834 brought him to Thessaloniki to run the family business.

“Moïse Allatini was a man who reached maturity in Italy at a time when 18th-century Enlightenment had been absorbed by the cultured bourgeoisie, when the ideas responsible for the French Revolution were fermenting among the students, and when the ancient regime had been supplanted by the Napoleonic Empire.

He brought the industrial revolution [to] Thessaloniki when he set up the Allatini mills, and later a brickworks, a brewery and a tobacco factory. At the same time he opened the doors to the cultural revolution.”

Moise Allatini was one of the first industrialists in Salonica to challenge the wealthiest in the community as well as their religious leaders.

Concerned about the fate of the Jewish people in his community whose living, working, economic and educational conditions were deplorable, Moïse Allatini became convinced that through education he could bring about the betterment of society. In order to improve the current state of affairs and help people become modern enlightened citizens, it was necessary to bring them out of ignorance by means of education.

In collaboration with other important families from Livorno, Italy — such as the Misrachi, Fernandez and Modiano families— Moïse Allatini became committed to modernizing and westernizing the educational system.

Prominent activists of the Haskalah, the intellectual movement which sought modernization of Jewish life. Operated circa 1770-1880. image by ביקורת: Raphael Levi Hannover, Solomon Dunno, Tobias Cohn, Marcus Elieser Bloch, Salomon Jacob Cohen, David Friedländer, Naphtali Hirz Wessely, Moses Mendelssohn, Judah Löb Mieses, Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport, Joseph Perl, Baruch Jeittels, Avrom Der Gotlober, Abraham Maps, Samuel Joseph Fuenn, Isaac Baer Levinsohn.

The Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment (Hebrew: השכלה; literally, "wisdom", "erudition" or "education"), was an intellectual movement among the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe, with certain influence on those in Western Europe and the Muslim world. It arose as a defined ideological worldview during the 1770s, and its last stage ended around 1881, with the rise of Jewish nationalism.

“In 1837, he founded the firm of Allatini Frères, which later became Allatini and Modiano. The company managed the assets of the Darblay de Corbeil family, bought shares in mills, and was engaged in various other business enterprises.

Under his leadership, the Allatinis amassed capital and dealt directly with Europe’s wealthiest Jewish families, such as the Camondos and the Rothschilds, as well as the Sassoons of Baghdad.

With the collaboration of the Länderbank in Vienna, Allatini founded the Allatini Bank and opened branches in cities around Salonica. His only competitors were the Saül Modiano Bank and the Ottoman Bank.

In addition to banking, Allatini built a large steam-operated mill and brick factory in Salonica; opened beer, tobacco, soap, and bed linen factories; started a workshop for silkworm breeding; and invested in chrome, manganese, and pyrite mines in Serbia.”

The Kaput Hesed Olam

In 1853 Moïse Allatini was the central figure in a group known as “the Illuminati” (known in French as “les Eclairs”).

“A notable first attempt at educational reform occurred during the 1850’s with the formation of the Hesed Olam Fund, created by Moise Allatini.”

The Kupat Hesed Olam (Mutual Welfare Fund), founded in 1853 by Moïse Allatini, aimed to reform the medical and educational systems and provide assistance to the unemployed by taxing Jewish merchants on their transactions.

“Sa’adi [Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi] holds Moise Allatini and his efforts to open new modern Jewish schools in high regard. He writes, “In an attempt to bring civilization to the people of Salonica, the tireless and enthusiastic ... Moizé Allatini... thought of creating a special fund, called Hesed ‘Olam.”

The efforts put forth by Allatini indicate that he did not simply want to educate, rather he saw a need to civilize his community by means of improved education.”

“In 1856 this body brought a young rabbi from Strasbourg to reform the central educational institution in Salonika, the great Talmud Torah, and to give evening classes in foreign languages and arithmetic; this effort lasted for five years and ended in failure, because of rabbinical opposition. Still the seeds of change had been planted.”

Alliance Israélite Universelle

“Along with the Morpurgo and Fernandez families, [Moïse] Allatini organized a group of visionary notables who helped to reform communal institutions in Salonica. In spite of a conflict between Allatini and Chief Rabbi Covo and other rabbis, they were able to establish a Hebrew school and a society for medical care (Heb. biqqur ḥolim).

In 1858, Allatini founded a French school, and hired a modern rabbi from Strasbourg as its principal, in an attempt to compromise with the religiously observant segment of the community. The school was forced to close after only five years, but during that time educated a great many children.

Allatini did not give up, and in 1873 he opened a school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle for boys of all faiths, which admitted 210 students in its first year of operation.

He then founded another school for girls, and a third, professional school. ”

In 1856, with the help of the Rothschilds, consent from the rabbis and generous charitable donations, Allatini established The Lippman School, an institution headed by Professor Lippman, a progressive rabbi of Strasbourg. Five years later, Lippman left under pressure from the rabbinate who disagreed with his innovative methods of education. However, he had had time to train many of the students who later took over.

In 1862, Dr. Allatini urged his brother-in-law Salomon Fernandez to found an Italian school thanks to a donation from the Kingdom of Italy.

Several attempts to establish the educational network of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) failed under pressure from rabbis who did not accept that a Jewish school could be placed under the patronage of the embassy of France.

But the need for educational structures became so pressing that the supporters of its establishment finally won their case in 1874 thanks to the patronage of Allatini who became a member of the central committee of the Alliance Israélite Universelle in Paris.

The network of this institution then expanded rapidly: in 1912, there were nine new IAU schools providing for the education of both boys and girls from kindergarten to high school while rabbinical schools were in full decline. This had the effect of permanently implanting the French language within the Jewish community of Thessaloniki as well as throughout the Eastern Jewish world. These schools dealt with the intellectual but also manual training of its students, allowing the formation of a generation in tune with the evolutions of the modern world and able to integrate the labor market of a society in the process of industrialization.

In 1857 Moïse Allatini built the first modern flour mill in Salonica and in 1873, the first Alliance Israélite Universelle school.

Old postcard showing the Allatini Mills

“Nowhere the work of Alliance Israélite Universelle was more successful than in Salonika. It was supported and facilitated by the presence in the city of a significant group of Francos (...).

By the nineteenth century families as the Allatini, Fernandez and Modiano were some of the most successful entrepreneurs in Salonika. In touch with developments in Western Europe, intermediaries for and partners of Jewish economic interests there, they were the first to realize the significance of the growing economic presence in the Ottoman Levant of modern European capitalism. The Anglo-Ottoman trade convention of 1838 opened local markets to finished manufactured products of the rapidly industrializing West. Port cities in the Eastern Mediterranean grew quickly in this period, which also saw the increased use of steamboat after the Crimean War.

The ability to speak French, the lingua franca of trade and commerce, became an increasingly desirable skill. And the Francos spearheaded efforts to teach through Western-style education. Franco notables, such as the bankers and industrialists Moise Allatini and Salomon Fernandez [Moise’s and Darius’s brother in law], working closely with the modernizer Judah Nehama, opened new schools in Salonika even before the arrival of the Alliance Israélite Universelle. ”

Sadi Levi, founder of La Epoka

“Between 1874 and 1875, the first newspaper in Ladino, La Epoka, was created under Allatini’s sponsorship, and it continued to publish until 1912.

Every year, Allatini donated part of the profits of Allatini Frères to schools, hospitals, and charities of all faiths in the city, and in appreciation was nicknamed “the saving angel of the Salonica community.””

honouring Moïse Allatini

Dr. Allatini was awarded the Medal of Honour by the government of Turkey (the Majidi'i (Medjidie) of the highest degree).

The government of Greece gave him the honorary title of “Salvatori”.

The Italian government decorated him with the title Knight of the Crown, “Cavaliero” of the crown of Italy.

He was also honoured by the Alliance Israélite Universelle for services rendered to his community.

From the government of Austria he received the decoration of a Knight of the Order of Franz Josef (Ritter des Kaiserlichen Franz Joseph-Ordens)

Jehiel was “venerated by all the scholars of his time”.

Interior of the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam, Emanuel de Witt, 1680, Rijksmuseum

“The earliest family member on record, Isaac Allatini (Alatin), was the rabbi of the Lisbon congregation in Salonica around 1512, soon after the expulsions from Spain and Portugal, which began in 1492.

Three Alatino brothers Jehiel, Vitale (or Ḥayyim), and [Moïse] Moses Amram, were physicians in Italy in the sixteenth century.

Jehiel settled in Todi, in central Italy. Vitale (d. ca. 1577) lived mostly in nearby Spoleto, where he practiced medicine from 1531 to 1552, and was called to attend Pope Julius III.

[Moïse] Moses Amram (ca. 1529–1605), moved to Ferrara in the mid-sixteenth century, and was most famous for his translations from Hebrew into Latin of Avicenna, Aristotle, and Galen’s commentary on Hippocrates.

David de Pomis (1525–1593), a nephew of the Alatino brothers, earned his medical degree in Perugia in 1551, in part thanks to an education provided by his uncles Jehiel and Moses Amram. ”

Mount Sinai, El Greco, 1570-72, Historical Museum of Crete

Azriel Perahiah Bonajuto Alatino, Moïse Amram’s son, an early ancestor of Moise Allatini, was a scholar and physician who became a rabbi around 1600.

He is famous for engaging in a debate on the Mosaic law with the Jesuit Alfonso Ceracciolo in Ferrara in 1617.

Moise Allatini’s father was Lazaro Allatini (1776–1834), a physician, born in Livorno Italy.

Lazaro studied medicine in Florence and moved to Salonica in 1796 where he married Anna Morpurgo (1783–1867), daughter of one of the richest local families.

Lazaro Allatini, miniature portrait; photo © Amanta Scott

The Morpurgo family

Anna Morpurgo’s ancestors came from Marburg, Hesse.

In the 15th century facing anti-Jewish persecution in Hesse, they took shelter in Friuli, an area of north-eastern Italy.

In 1732 Anna Morpurgo’s grandfather David Morpurgo appears in the official reports of the Venetian Consulate in Thessaloniki, as a leading personality of the Jewish community of the city and a protégée of France. He exported tobacco, and later cotton and wool to Ancona or Venice, even in the mid-18th century.

Anna Morpurgo’s father, David, was a protégée of Spain.

The Idol Arcade at Salonika, from J. Stuart and N. Revett, The antiquities of Athens, 1794 (Private collection, Salonika).

“Based in Friuli, the Morpurgo family established a branch of their company in Thessaloniki in the early 18th century and for a long time they enjoyed French and Dutch diplomatic protection for their commerce.

They bought the wool from the Jewish merchants of the city and exported it to Italy and France.

They became dominant in the market because they did not hesitate to pay higher prices than their competitors and by the middle of the 18th century they had accumulated enough capital to be envied by all the members of the French community in Thessaloniki.”

The Allatini Family

Lazaro Allatini and Anna Morpurgo had three sons, Moïse (1809-1882), Darius David (1820-1887) and Salomon (1825-1892); and four daughters, Rachelle (1817-1867), Benvenuta (1818-?), Myriam (1824-1894) and Rosina (Rosa) (d.1879).

The Allatini flour-mills

Picture postcard of the steam-driven Allatini flour-mills, where large quantities of grain were ground before being shipped through the port of Thessaloniki, 1898-1917, Thessaloniki, G. Megas archive.

In 1802 Lazaro took over his father’s business in Thessaloniki.

Lazaro died in 1834 after having started various businesses in Thessaloniki: a brick factory, a flour mill, and a tobacco factory. His seven children honoured his memory by building him a monumental tomb with an epitaph in Italian and Hebrew.

His eldest son, Moïse then took over running the family business.

Moïse Allatini married Rosa Mortera (1819-1892) and together had five sons: Lazaro, Emile, Hugo, Carlo (1851-1910) and Roberto; and a daughter, Annette.

Fratelli Allatini

In 1837 Moise, Darius and Salomon founded Fratelli Allatini (Allatini Brothers) as the family business became known.

By the nineteenth century the Fratelli Allatini and their brothers-in-law, Salomon Fernandez and Abraham Misrachi were some of the most successful entrepreneurs in Salonika.

Later they became known as Allatini and Modiano.

Allatini brick, Thessalonika, photo credit: Протогер

“The company managed the assets of the Darblay de Corbeil family, bought shares in mills, and was engaged in various other business enterprises.

Under [Moïse’s] leadership, the Allatinis amassed capital and dealt directly with Europe’s wealthiest Jewish families, such as the Camondos and the Rothschilds, as well as the Sassoons of Baghdad.

With the collaboration of the Länderbank in Vienna, Allatini founded the Allatini Bank and opened branches in cities around Salonica. His only competitors were the Saül Modiano Bank and the Ottoman Bank.

In addition to banking, Allatini built a large steam-operated mill and brick factory in Salonica; opened beer, tobacco, soap, and bed linen factories; started a workshop for silkworm breeding; and invested in chrome, manganese, and pyrite mines in Serbia.”

MOISE ALLATINI’S FAMILY

Jewish Woman in Thessaloniki, late 19th century, public domain

Allatini Brothers became famous not only as grain and tobacco exporters, but also as the largest shareholders of the Eastern Investment Company, a mining operation specializing in South African mines.

In Thessaloniki, Allatini Brothers operated three mines: an ore mine; a magnesite mine; and a chrome mine. All of these appear to have vanished in the war.

During the 1860s besides exporting Macedonian grain and tobacco to England, Allatini Brothers also imported grain from Ukraine into the London market.

Holland Park Avenue — London

From Thessaloniki, by the 1870s, an extensive branch of the Allatini family relocated to London, England, converging with the Rapoport family as well, on Holland Park Avenue, a select and expensive street in Kensington.

A postcard showing Royal Crescent in Holland Park West.

The postcard belonged to Emily Pauline Johnson (1861-1913)

18 Holland Park W11

35 Holland Park W11

The new couples, shaped by intermarriages between the families, made their homes at 18, 35 and 85 Holland Park.

“The emblematic figure of this extended family was Lazaro. Married to the offspring of an Italian family, named Emma Carolina Forti, Lazaro developed strong connections with Italy, due to commercial links as well as to charities for Italian philanthropic activities in England.

In 1893 he was elected President of the Italian Chamber in London and in 1901 he was appointed Consul-General of Italy. ”

By 1895 they were joined by Roberto and Bronislawa.

The other members of the family’s branch in London were Hugo (Darius’s son-in-law) and Robert, both Lazaro’s brothers, as well as Edward, Lazaro’s nephew and son-in-law. From an entrepreneurial point of view, these men were well known for their achievements in tobacco trade and mine exploitation.

Carlo (Charles) Allatini (1851-1910) —

Moïse’s son, Carlo married his cousin Ida Fernandez, the daughter of Salomon Fernandez and Bienvenuta Allatini, Moise’s sister.

Upon Moïse’s death in 1882, Carlo took over the family business, and in 1888, with his brothers, Roberto, Lazaro, Emile and Hugo, founded the Bank of Salonica.

Former headquarters of the Bank of Salonica in Thessaloniki, photo © JanLandschreiber

“This marked the culmination of the family’s business activity; the bank, whose revenue came from other Allatini companies that produced raw materials for family manufacturing interests, dominated all the family firms.”

In 1898 Carlo commissioned the famous Villa Allatini, designed by the Italian architect, Vitaliano Poselli, who also designed the Allatini Mills and the Beth Saul Synagogue.

Thessalonki Prefecture building, Villa Allatini, former residence of Allatini family

The Beth Saul Synagogue

Patrons of the Allatini Jewish Orphanage pose with some of the children in March, 1936.

“The Jews recreated 15th century Spain in Salonika but, due to restrictions imposed by the Ottoman authorities as to site and size, in the 19th century their synagogues were limited to simple rectangular halls, often in side roads concealed from public view, in no way comparable to the Mudéjar-style structures of Toledo, Cordoba, and Segovia.

[...]

The [Beth Saul] synagogue was designed by the Italian architect Vitaliano Poselli [ . . . ] sent to Salonika by the Ottoman government to design state-sponsored buildings which were to ‘cloth in stone’ the major reforms: clearly visible from various viewpoints and combining principles of symmetry and regularity, these western-inspired structures were to give a progressive modern aura to a centuries-old city.

While the earlier synagogues were modest structures along blind alleys, or placed in upstairs rooms, but always an integral part of the urban fabric including auxiliary spaces and community institutions, the Beth Saul stood alone in a garden next to the new family mansion (Villa Ida, V. Poselli, 1886-90). ”

Salonika Occupation

Roberto Allatini (1856-1904) & Bronislawa Rapoport von Porada

Moïse’s son, Roberto Allatini (my great grandfather) was a merchant and a banker, who lived in Salonica, Vienna and London.

Roberto married Bronislawa Rapoport von Porada (my great grandmother) who came from what is said to be the most important of all the non-chasidic rabbinic dynasties, in Ukraine.

At some point Roberto and Bronislawa were living in Vienna in a vast home with a great many family members.

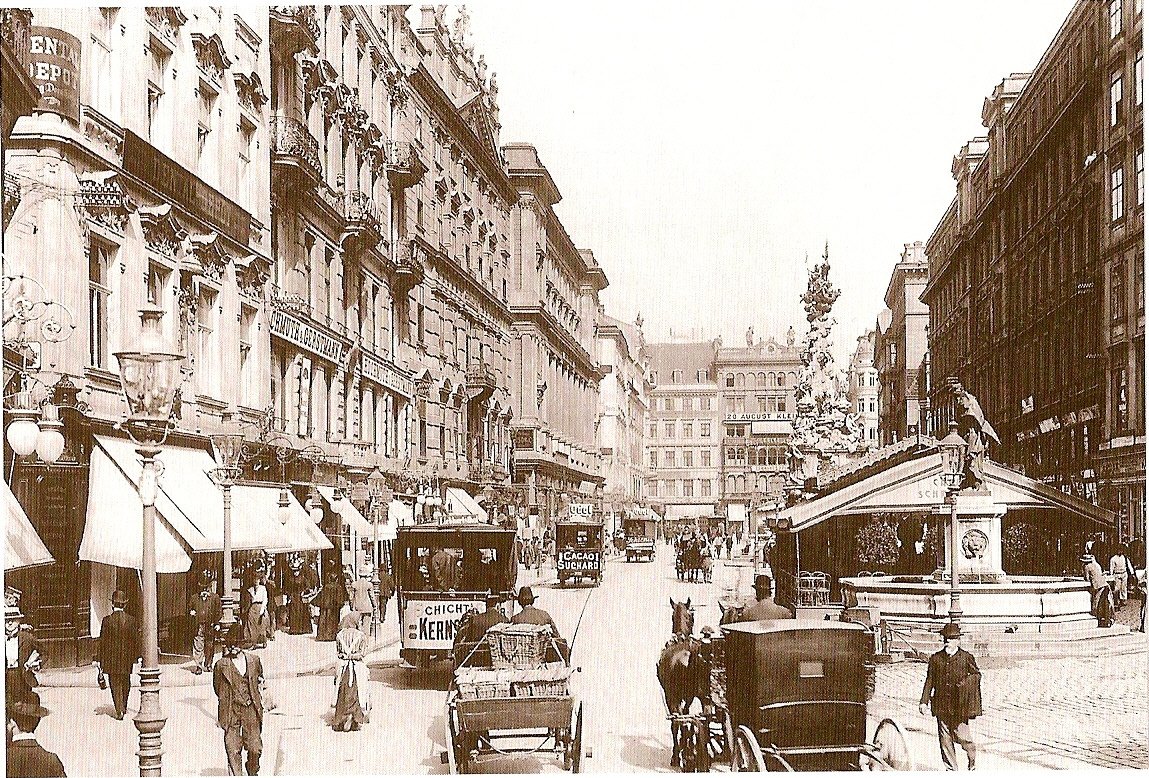

Wiener Graben Straßenansicht / View of The Graben, Vienna, Exhibition Catalogue of the Vienna Museum: Eye-catchers of a trip to Vienna: photo Josef Löwy

Roberto and Bronislawa had two daughters: Rose Laure Allatini, my granny, born in Vienna in 1890; and Flora Allatini, born in London five years later when the family moved to England, where Roberto ran the London office for Fratelli Allatini.

Hugo & Beatrice Allatini

Also on the Avenue lived Roberto’s brother, Moïse’s son, Hugo who had married his cousin, Beatrice, Darius’s daughter. (Sadly Beatrice died at a young age, leaving her husband with two baby daughters)

. . . and . . .

Annette Allatini & Darius Allatini

Roberto’s sister, Moïse’s daughter, Annette who had married her cousin, Edward, Darius’ son, also lived on the Avenue. There, Edward ran a branch of the family company dealing with tobacco commerce. The couple had four children. Darius David (1872 - 1920); Rosine (1874 ~ 1942); Béatrice Aime (Amy) (1881 - 1913); and Eric Moise (1886 - 1943).

Eric Moise Allatini & Helene Hirsch-Kahn

Eric Moise Allatini and his wife Hélène Hirsch-Kahn were arrested in Paris and deported without return from Drancy to Auschwitz by convoy no. 63 and murdered in Auschwitz on December 17th 1943.

“During the summer of 1943, the two youngest Allatani daughters, Donatella, born in 1926, and Tiziana, born in 1927, took refuge with Jeanne Talon, a trusted friend of their mother.

The two older children of Eric and Hélène Allatani, Jocelyne Julie Milisand, born in 1918 (who died in 1947) and Ariel Aimond Alvise, born in 1921, who had joined the maquis, were not deported.

Towards the end of November 1943, two of the girls’ cousins, Violaine Reinach, 18, and her sister Laurence, 15, arrived at Jeanne Talon’s home.

Their parents, members of the Camondo family, were arrested and interned at Drancy. They were deported to Bergen-Belsen.”

Emile Allatini

Moïse’s son, Emile, a civil engineer, married Mathilde, Darius’ daughter. Born in Thessaloniki, they lived in Paris.

Lazaro Allatini

Moïse’s son, Lazaro, was initially head of the London office of Allatini Brothers. Lazaro married Emma Carolina Forti, from an Italian family with strong commercial connections and links to charities for Italian philanthropic activities in England.

In 1893 he was elected President of the Italian Chamber in London and in 1901 appointed Consul-General of Italy.

The Allatini’s were wealthy, cosmopolitan and Jewish. They had extensive interests in the Eastern parts of Europe and had been doing business in London since at least the 1860s, arranging the export of Macedonian grain and tobacco to England and also grain from the Ukraine. By the 1870s a branch of the family, headed by Lazaro Allatini, was based at Holland Park Avenue, Married to an Italian and with strong commercial, social and philanthropic links to Italy, Lazaro was in 1893 elected President of the Italian Chamber in London and in 1901 he was appointed Italy’s Consul-General in London. Lazaro’s brother Robert born in Thessaloniki in 1856 was a prosperous tobacco trader. he married Bronislawa…. The 1891 census shows them living at 18 Holland Park.

Portrait of Bronislawa Rapoport Edlen von Porada, by Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz, photo © Amanta Scott

Bronia’s great grandfather was Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport, a religious scholar, rabbi, poet and writer.

Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport married Franziska Freide Heller, daughter of Rabbi Aryeh Leib Heller, a renowned scholar and direct descendant of Rabbi Yom-Tov Heller — one of the major Talmudic scholars in Prague and Poland during the Golden Age.

Rabbi Heller was accused of insulting Christianity and imprisoned in Prague.

Bronia’s father, Arnold Rapoport Edlen von Porada was a lawyer, parliamentarian, coal mining entrepreneur, and a philanthropist. He was knighted by Austrian Emperor Francis Joseph and awarded the Turkish Order of the Medjide, first class; and the Serbian Order of St. Sawa.

Bronisawa’s sister, Felicia von Kuh, is pictured here in a now-lost portrait painting by Philip Alexius de László, 1904. Philip Alexius de László was an Anglo-Hungarian painter known particularly for his portraits of royal and aristocratic personages. In 1900, he married Lucy Guinness of Stillorgan, County Dublin and he became a British subject in 1914. László was born in humble circumstances in Budapest as Fülöp Laub, the eldest son of Adolf and Johanna Laub, a tailor and seamstress of Jewish origin.

Bronislawa’s sister, Felicia von Kuh (née Rapoport von Porada), by Philip Alexius de László, 1904

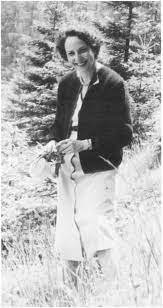

Rose Laure Allatini, my grandmother. Image © Amanta Scott

Flora Allatini (1895-1941), Rose’s sister, married Matthew Talbot Baines. They had two children, Sonia and Babette.

Helene Hirsch-Kahn Allatini, Oskar Kokoshka, 1909, Kunsthaus Zurich

«MalletStevens.CasaAllatini». Vía Urbipedia

Allatini House, designed by Robert Mallet-Stevens between 1925 and 1927, was built for filmmakers Hélène Kahn and Eric Allatini. Allatini house is a large four storey mansion with a cinematographic projection room, in Paris.

Moise Allatini’s siblings

Rachelle (1817-1867)

Moïse’s sister Rachelle married a member of the Morpurgo family, Moise Morpurgo, believed to be the brother of her mother.

Her grandson, Moise Morpurgo Jr. (1860-1939) served as CEO of the Société Anonyme Industrielle et Commerciale, the main company of the Allatini family.

Benvenuta (1818-?)

Moïse’s sister Bienvenuta married Salomon Fernandez (1811-1894).

Two of Lazaro’s daughters, and one of his sons, married into the wealthy Fernadez family on Constantinople. Gustave Fernandez Allatini, a grandson of Lazaro Allatini, through Bienvenuta Allatini, and his wife Pauline, a granddaughter of Lazaro Allatini, thought Darius David Allatini, had been living in Paris for many years when Joyce arrived there in 1920. Gustave was born in 1854 in Salonika and when a young adult, moved to Marseille where he truncated his name to Fernandez. In Marseilled, he met and married Pauline, born there in 1865. There were three Fernandez children, all. native Parisians: Emile, Eva and Yolande. Joyce met the young Eva shortly after arriving in Paris, most likely at the bookshop Shakespear & Company. By October 1920 Joyce had persuaded her to translate in French “A Most Delicate Case” from his collection of short stories, Dubliners. The Fernanxez family was highly cultured and among their regular visitors, including Joyce and his teenage children were the Avantgarde of Paris. mme. Fernandez was hostess to Jean Cocteau, Eric Satie, Francis Poulenc, Darius Milhaud (a relative), and Jean Renoir, among others. When Joyve visited he spent most of his time ther engaged with the family matriarch, while Lucia paired off with Yva and Giorgio with Emile. The extended Fernandez family viewed Yea somewhat askance as “she was in advance of the ideas of a very bourgeois epoch.

Molly Bloom: Daughter of the Regiment, The British Army in Ulysses: Volume 2 of the British Army on Bloomsday, By Peter L. Fishback

Darius David Allatini (1820-1887)

Moïse’s brother Darius married Hanna Armine (Annina) Moise Fernandez who came from a Franco family from Livorno, Italy. Commercially active in Thessaloniki, the Fernandez family became rich merchants tax farming and exporting coal, grain and salt.

Darius and Armine had seven children: Edward (1847-1913), Alfred (1849-1901), Beatrice (1856-1880); Mathilde (1854-1917), Noémie (1860 - 1928), Pauline (1865-1949) and Sophie (1868-1943).

Darius David Allatini’s sons & daughters

Except for their daughter Noemie, Darius and Armine married off all their children to the children of his brothers, Moise and Salomon. Three of Moise’s children married the children of Moise’s brother, Darius.

Alfred, son of Darius David Allatini, married Adele-Sarah, daughter of Salomon. Living in Thessaloniki, where Alfred ran the family’s mill, they had two daughters: Anna Berthe and Emma (1896-1944) who was murdered in Auschwitz.

Éliane Amado Levy-Valensi

Emma Allatini’s daughter was the French Israeli psychologist, psychoanalyst and philosopher Éliane Amado Levy-Valensi (1919-2006).

General Darius Paul Bloch

His brother, Marcel Ferdinand Dassault, survived Buchenwald, where he was tortured, beaten and held in solitary confinement. Marcel was a French inventor, engineer and industrialist who invented the French Air Force’s first jet aircraft, launched Dassault Aviation and created the Mirage Fighter Jet. Marcel was awarded France’s highest honour, the Legion of Honour’s Grand Cross.

Noémie married Adolph Bloch, a 33 year old doctor from Strasbourg, son of the banker Luis Bloch, and a distinguished scholar. Bloch published a number of medical and scientific studies in international magazines. Noémie and Adolph Bloch had four children: Jules André Albert (1879-1926), Darius Paul Bloch (1882-1969), Marcel Bloch (1892-1986) and René Bloch.

Darius David Allatini’s grandson, Darius Paul Bloch, was a general in the French Resistance.

Sophie Milhaud Allatini (1868 - 1943) was the mother of Darius Milhaud (1892-1974), a French composer, conductor and teacher. He was very close to his fist cousin, Eric Allatini and Eric’s wife Hélène Allatini-Kahn.

Darius Milhaud was a member of Les Six—also known as The Group of Six—and one of the most prolific composers of the 20th century.

His compositions are influenced by jazz and Brazilian music and make extensive use of polytonality. Milhaud is considered one of the key modernist composers.

A renowned teacher, he taught many future jazz and classical composers, including Burt Bacharach, Dave Brubeck, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis.

Darius Milhaud, 1926

Salomon Allatini (1825-1892)

Moïse’s brother Salomon married Sophie Moro (1876). They had four children, Frederic, Guido, Anna, and Adele.

Anna married Achilles Bloch, the brother of Dr. Adolph Bloch, husband of her cousin Noémie Allatini Bloch.

ROSA Allatini (1879-?) — Moise Allatini’s sister

Moïse’s sister Rosa married Moïse Fernandez.

Their daughter Elise Fernandez Allatini de Camondo (1840-1910) married Comte Nissim de Camondo (1830-1889), from a prominent European family of Jewish financiers and philanthropists. See House of Camondo.

Comte Nissim de Camondo, 1882, Carolus-Duran (Charles August Emile Durant) 1837-1917, Musee Nissim de Camondo

Their son, Comte Moise de Camondo married Iréne Cahen d’Anvers.

Renoir’s famous painting « Portrait of Irène Cahen d'Anvers » was commissioned by her father, Louis Cahen d’Anvers, who apparently so disliked the work that he hung it in the servants quarters and delayed Renoir’s payment of 1500 franks. Needless to say Renoir was highly offended.

Eleven years later Iréne Cahen d’Anvers married Moise Allatini’s grandson, my cousin Comte Moise de Camondo, a French banker and collector of 18th century French furniture and artwork.

The portrait was then hung in their matrimonial home which he had meticulously designed.

Together they had two children, Nissim (1892-1917) and Beatrice (1894-1945. Irène then had an affair with the stable master and left Comte Moise de Camondo with the kids.

When his son, Nissim, was killed fighting in WWI, Moïse was devastated and withdrew from society.

Later Comte Moise de Camondo donated his mansion to the city of Paris, as the Musée Nissim de Camondo.

Musée Nissim de Camondo, Paris, France - Grand Salon, image: Daderot, public domain

In WWII, his daughter, Beatrice and her children were murdered in Auschwitz.

As a result Irène inherited the Camondo fortune which she apparently squandered on the racetrack.

Portrait of Irène Cahen d'Anvers, Renoir

War years

By 1911 all members of the Allatini family who resided in Thessaloniki were Italian subjects. With the outbreak of the Ottoman-Italian war that year, all remaining Allatini were expelled from Thessaloniki.

In August 1917 a great fire destroyed much of Thessaloniki.

In World War Two the Allatini/Rapoport family home in Vienna was commandeered as Hitler’s headquarters. Given 30 minutes to flee the country, some of the family escaped, but many were sent to the concentration camps. There, most of them were exterminated: their belongings lost to the Nazis.

One who did manage to escape and tell the story, was Edith Porada, an art historian and archaeologist. In 1938 she emigrated to the United States where she worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the seals of Ashurnasirpal II.

Edith Porada, 1912-1994

Edith was a leading authority on ancient cylinder seals and a professor of art history and archaeology at Columbia University. Born in Vienna 1912, she died in Honolulu in 1994. Edith graduated from the Realreform Gymnasium Luithlen in 1930 and received her Ph.D. from the University of Vienna in 1935 with a dissertation about glyptic art of the Old Akkadian period.

In 1976 she was awarded the Gold Medal Award for Distinguished Archaeological Achievement from the Archaeological Institute of America. Columbia University established an Edith Porada professorship of ancient Near Eastern art history and archaeology with a $1 million endowment in 1983.

In 1989 Porada was awarded Honorary Degree of Doctor of Letters for Columbia for "profound connections between the human experience and the interpretation of the cylinder seals."

“During the German occupation his tombstone was destroyed to its base by the Greeks, who did not remember [Moise Allatini’s] righteousness and good deeds towards members of their nation as well.”

“The eminence of the Allatini family in Salonica continued until the early twentieth century, when the Balkan wars and antisemitism led to the sale of its assets and the emigration, in 1911, of most of its members to other parts of Europe.

A number of buildings in Salonica still bear their name. The descendants of the Allatinis in France, England, Italy, and Israel continued to be scholars and artists throughout the twentieth century.

The Allatini family reflects the transmission of a cultural tradition across centuries and generations, a chain made up of significant figures who marked their times and impressed their contemporaries.”

References

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/History_of_the_Jews_in_Thessaloniki

- https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/219/singing-gentile-songs-a-ladino-memoir-by-saadi-besalel-a-levi/

- https://www.academia.edu/2306815/The_immortal_Allatini_Ancestors_and_Relatives_of_Noemie_Allatini_Bloch_1860_1928_

- https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/thessalonika/thev1_014.html

- http://railwayheritage.blogspot.com/2015/04/allatini-allatini-brickworks-railway.html

- https://travelthegreekway.com/eastern-thessaloniki-jewish-monuments-part-ii/

- https://www.mic.com/articles/183842/this-lively-greek-city-is-known-as-the-city-of-ghosts-for-its-forgotten-jewish-history

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allatini_Mills

- https://esefarad.com/?p=95926

- https://www.studylight.org/encyclopedias/eng/tje/a/alatino.html

- http://www.jcrpolemicsinitaly.at/treatises.html

- https://gettingontravel.com/museum-of-italian-judaism/

- https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopedia-of-jews-in-the-islamic-world/allatini-family-SIM_0001570

- https://www.quest-cdecjournal.it/in-search-of-salonikas-lost-synagogues-an-open-question-concerning-intangible-heritage/

- http://www.sephardicstudies.org/thes3.html

- https://thessarchitecture.wordpress.com/2016/05/19/μυλοι-αλλατινη/

- http://thessalonikijewishlegacy.com/villaAllatiniDescriptionEN.html

- https://www.sfarad.es/los-alatini-1a-fortuna-de-salonica-y-3a-del-imperio-otomano/

- https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/material-civilization/first-world-war-european-disintegrations/italy’s-failed-project-trans-balkan-railway-“rome-valona-constantinople”

- https://war-documentary.info/holocaust-in-salonica/

- https://www.entreprises-coloniales.fr/inde-indochine/Induscom_Salonique.pdf

- https://www.enmanos.gr/images/pyrkagia.pdf

- https://segulamag.com/en/today_event/רבי-יום-טוב-ליפמן-הלר-נאסר-בעקבות-קנוני/

- https://tobiaspicker.com/opera/lili-elbe

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/24692921.2019.1573784?journalCode=rfmd20

- https://artsandculture.google.com/story/4wVRgoeMNBMA8A

- https://www.urbipedia.org/hoja/Casa_Allatini

- https://picryl.com/media/felicia-von-kuh-nee-rapoport-von-porada-by-philip-alexius-de-laszlo-1904-223fba

- https://www.delaszlocatalogueraisonne.com/catalogue/the-catalogue/search/gender:f-female/page/5

- https://history.barnard.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Sarah%20Sasson%20Jewish%20Education%20Thesis%20Final_1.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Epoka

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Age_of_Enlightenment

- https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Maskilim

- https://books.google.ca/books?id=e0GwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA19&lpg=PA19&dq=roberto+Allatini+in+vienna&source=bl&ots=AnIWE7Sp8K&sig=ACfU3U2J02gm91YqIao2z4D9HusryTKwhg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjc5fjH3c74AhXZHc0KHdNFCcgQ6AF6BAgfEAM#v=onepage&q=roberto%20Allatini%20in%20vienna&f=false

- https://books.google.ca/books?id=lh1REAAAQBAJ&pg=PA198&lpg=PA198&dq=lazaro+allatini&source=bl&ots=8PzAgHvvU3&sig=ACfU3U3caaE9JHyJrVP56_B-9s1_43fE3A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiV1PnL6M74AhVCJ80KHfKHDLsQ6AF6BAgXEAM#v=onepage&q=lazaro%20allatini&f=false

- https://history.stanford.edu/publications/jewish-voice-ottoman-salonica-ladino-memoir-saadi-besalel-levi