voyeurism

Depictions of women being watched by men in private moments is another favourite theme in art history and mythology.

Consider the Goddess known to the Greeks as Artemis and to the Romans as Diana: the embodiment of achievement and competence; independence from men and male opinions; and concern for victimized, powerless women and the young. The Olympian Goddess of the Moon, Goddess of Wildlife, of the Hunt and Chastity, Diana/Artemis roamed the wilderness, forests, mountains, meadows and glades with a band of nymphs and hunting dogs.

She is also known as the Goddess of Childbirth since she aided her mother, Leto in her own birth. Thereafter she was called upon to aid women in childbirth. Artemis is also one of the few goddesses who repeatedly came to the aid of her mother.

As Goddess of Wildlife she was associated with the attributes of many undomesticated animals, elusive and wary, regal and fierce. She acted swiftly and decisively to protect and rescue those who appealed to her for help and was merciless to those who offended her. An accomplished archer, she rescued many women who were at risk of being raped and was swift to slay the offenders with the deadly aim of her bow.

As the Virgin goddess, she represents the whole woman, complete in herself without the aid of a man. She was not raped and never married; although mistakenly she killed the one man she loved, Orion, because of her competitive nature.

One story often depicted in art history tells of a moment when the Goddess fell in love with the youth, Endymion. According to legend she would come and kiss him each night as he lay sleeping on top of the mountain. At one point her light touch briefly wakened him and he caught sight of her but he attributed this to a dream. Preferring the dream state to his dreary quotidian reality, he was never awake when she was present. Through her love Endymion was granted eternal youth and timeless beauty.

As Goddess of the Moon she is shown as a light bearer, carrying torches in her hands or with the moon and stars surrounding her head. She was at home in the night, roaming the wilderness by moonlight. In her Moon Goddess aspect, she was related to Selene and Hecate. She was the personification of the independent feminine spirit.

ETERNALLY DISRESPECTED: WATCHED BATHING

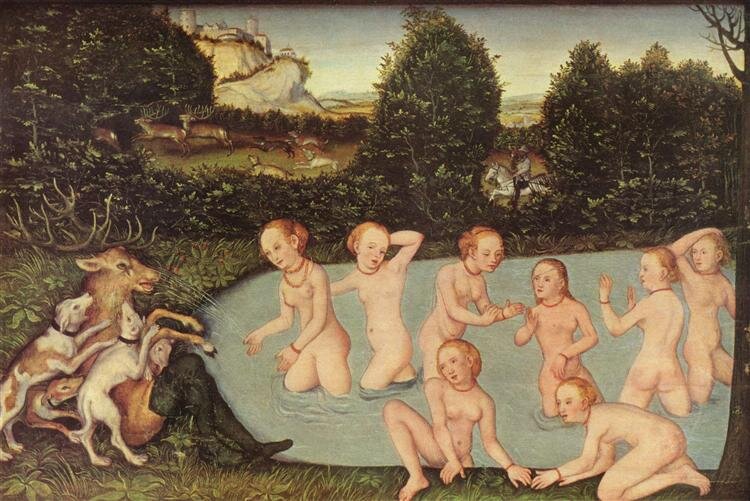

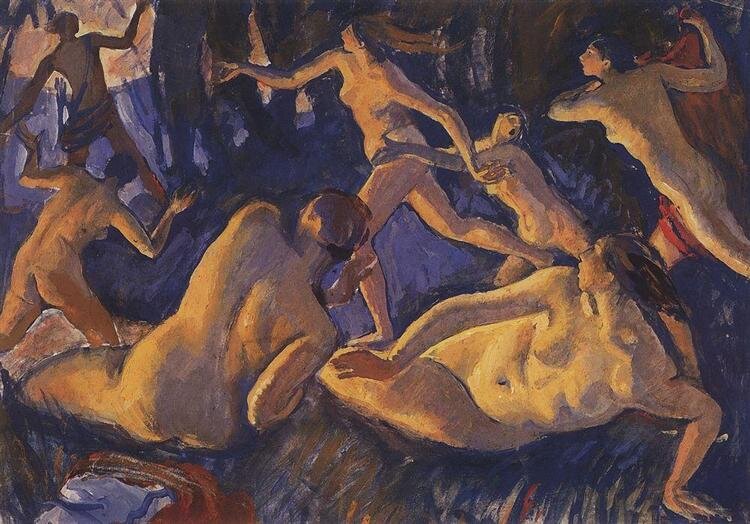

Given how revered and powerful Artemis was, it is interesting, troubling and psychologically revealing to note that the story of Acteon watching Artemis and her nymphs bathing has been painted and sculpted with such frequency, and almost always from the perspective of Acteon, exposing Artemis, forever, against her wishes. Was this an aspect of the Christian campaign against ancient Greek and pagan religions, attempting to dishonour her and diminish her power?

The story goes that Artemis caught the hunter Actaeon watching her and her nymphs bathing in a hidden pool. Furious at this intrusion, she splashed water into his face which turned him into a stag. As a result, Acteon, suddenly quarry for his own hunting dogs, was torn to bits.

The part of this story most frequently depicted in Art, however, is the moment when she is surprised, naked and vulnerable: not her subsequent rage. Such depictions enable and play into the eye of the voyeur — undermine the point that spying on a woman in a private moment without her consent is unacceptable and, in the eyes of a Goddess, punishable by death! Many paintings are titled “Artemis (Diana) surprised…” which is rather an understatement. How likely are you to kill someone if you are surprised? Artemis was enraged! She has been disrespected!

Such depictions enable and play into the eye of the voyeur — undermine the point that spying on a woman in a private moment without her consent is unacceptable and, in the eyes of this Goddess, punishable by death.

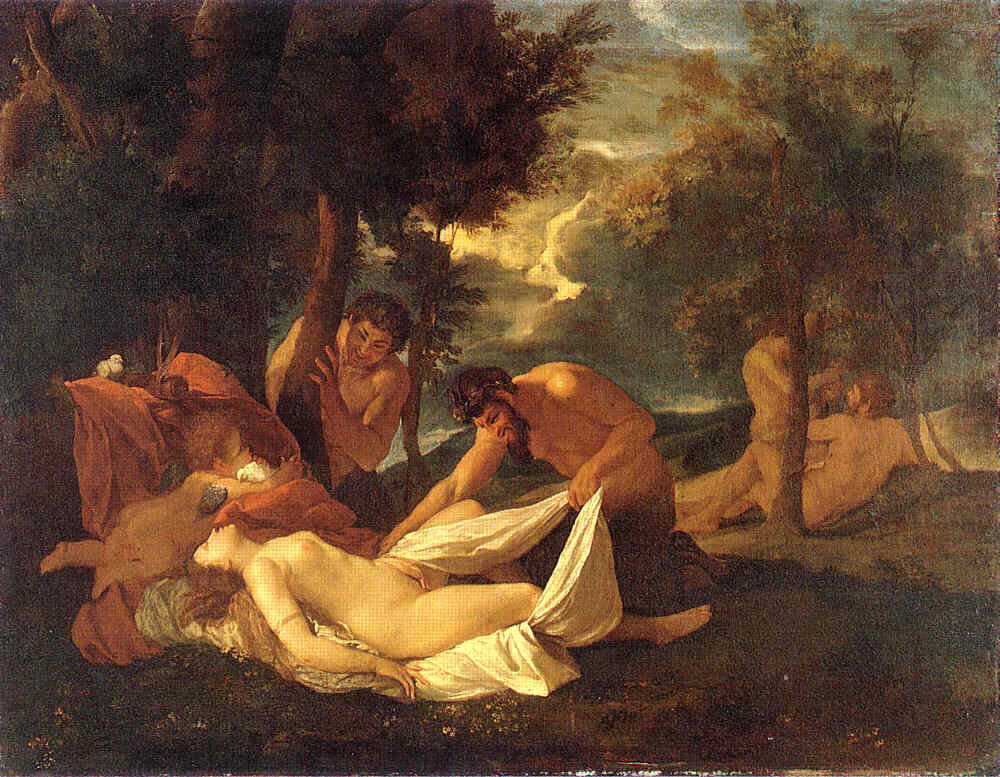

The magnitude of the paintings dedicated to this one story is amazing (these are but a few examples). This obsession with doing and depicting precisely what has been deemed unacceptable is fundamentally childish. Surely we can do better than that. Looking beyond childishness, this also seems like a calculated attempt at undermining the authority of the Goddess and a clear and continued demonstration of disrespect for women in general.

How long will we continue to accept this? How long will we further and enable voyeurism? There’s no question the works aren’t beautiful, nor that we shouldn’t continue to see them, however contextualizing these artworks as feeding into the voyeuristic gaze would be helpful if we have any interest in elevating human thought and behaviour.

Imagery is powerful. We learn from and imitate what we see.

The stories of Bathsheba, and Susanna and the Elders take the issue even further. So often the depictions include and make the viewer complicit in the secret viewing of a vulnerable woman.

Should we ask ourselves why, as a society, do we wish to continue enabling such behaviour?

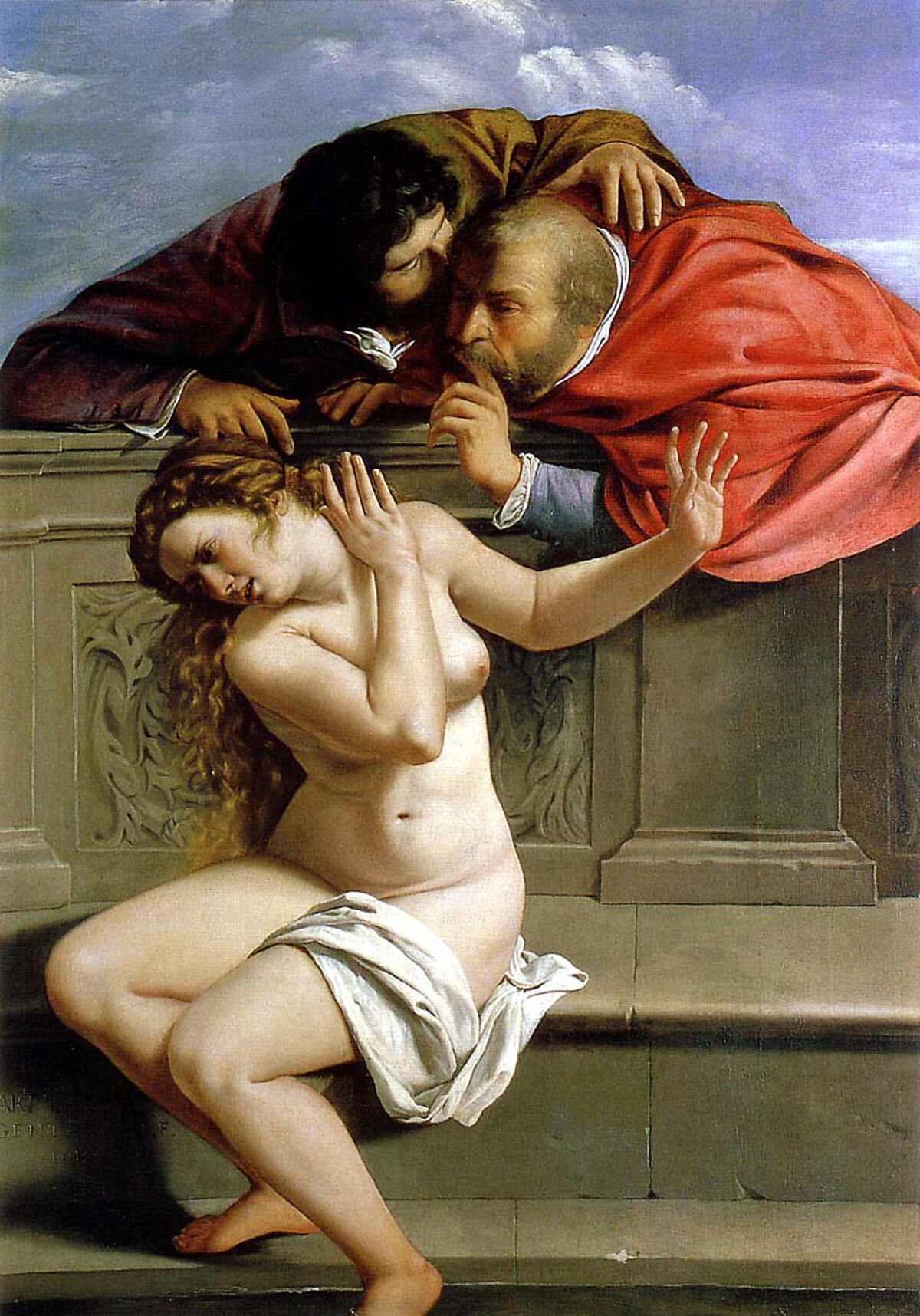

Consider the story of Susanna and the Elders

Susanna and the Elders is a Biblical story from the Book of Daniel (chapter 13). One of the additions to the Book Daniel, it is considered apocryphal by Protestants. Interestingly, it is listed in Article VI of the 39 Articles of the Church of England among the books which are read "for example of life and instruction of manners", but not for the formation of doctrine. [Wikipedia] The story tells how, during the captivity of the Jews in Babylon, a virtuous young woman was falsely accused of sexual promiscuity by two elders of the community who lusted after her themselves. The prophet Daniel exposed the two elders as liars and vindicated Susanna.

Susanna, a beautiful, married woman has sent her attendants away so that she may bathe alone in her garden. As Susanna bathes two lustful elders secretly observe the lovely woman. When she makes her way back to her house, they accost her, threatening to claim that she was meeting a young man in the garden unless she agrees to have sex with them. Susanna refuses to be blackmailed and consequently is arrested.

She is about to be put to death for promiscuity when suddenly a young man, Daniel, interrupts the proceedings, shouting that the elders should be questioned to prevent the death of an innocent. The two men are separated, and cross-examined about the details of what they saw. They happen to disagree about the tree under which Susanna supposedly met her lover. In the Greek text, the names of the trees cited by the elders form puns with the sentence given by Daniel. The first says they were under a mastic tree (ὑπο σχίνον, hypo schinon), and Daniel says that an angel stands ready to cut (σχίσει, schisei) him in two. The second says they were under an evergreen oak tree (ὑπο πρίνον, hypo prinon), and Daniel says that an angel stands ready to saw (πρίσαι, prisai) him in two. The great difference in size between a mastic and an oak makes the elders' lie plain to all the observers. The false accusers are put to death, and virtue triumphs.

It is interesting to note how painters throughout history have fixated on depicting the moment of the Elders spying on Susanna rather than on her exoneration — thus including the viewer in the supposed thrill of voyeurism, and underlining her vulnerability under the male gaze. Given the number of paintings of this subject alone, it tends to normalize the idea of voyeurism.

Something we could ask ourselves is: how do we feel about voyeurism, people watching us without our permission? Can we learn more compassionate and respectful behaviours from contemplating these beautiful artworks when we understand the pain this can cause?

SUSANNA IN MUSIC

Susanna (HWV 66) is an oratorio by George Frideric Handel, in English. Handel composed the music in the summer of 1748 and premiered the work the next season at Covent Garden theatre, London, on 10 February 1749. Recordings of Handel’s Susanna, HWV66

The American opera Susannah by Carlisle Floyd, which takes place in the American South of the 20th century, is also inspired by this story, but with a less-than-happy ending and with the elders replaced by a hypocritical traveling preacher who rapes Susannah.

Bathsheba

In a story from the Hebrew Bible, King David is out on the flat roof of his palace, when he sees a beautiful woman from a nearby house undressing and bathing herself. Passions excited, David, ever attracted by lovely women, enquires after her, and learns that she is Bathsheba, wife of Uriah. David nevertheless covets her, sends for her, makes love to her and impregnates her. Then, once he learns of Bathsheba’s condition, David, in an effort to conceal his sin, summons Uriah home from the army (with whom he is on campaign) in the hope that Uriah will make love to his wife and believe the child belongs to him.

Uriah, however, is unwilling break ranks in order to return home from battle and chooses to remain with the palace troops. Since David fails in his efforts to convince Uriah to have sex with Bathsheba, his next resort is to have Uriah sent to the front lines where he is sure to be killed. That job neatly completed, David marries Bathsheba. David's action is deemed displeasing to the Lord, who sends Nathan the prophet to reprove him. The king immediately confesses his sin and repents, however his first child dies immediately upon birth which David accepts as just punishment.

Venus

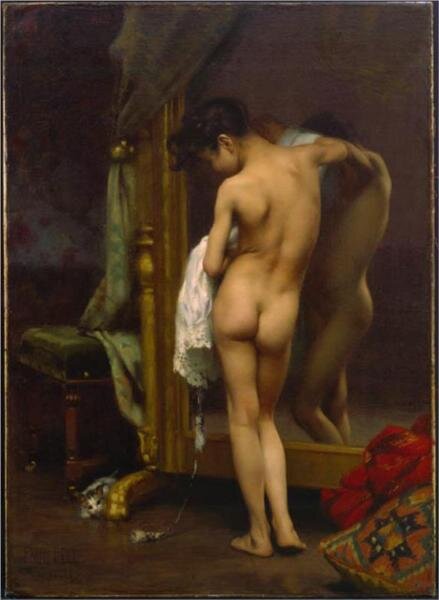

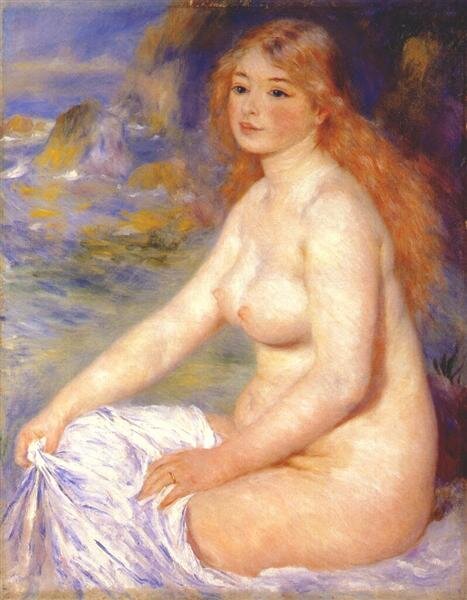

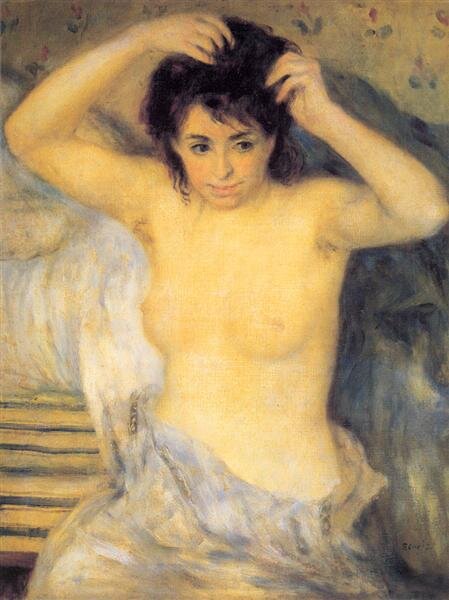

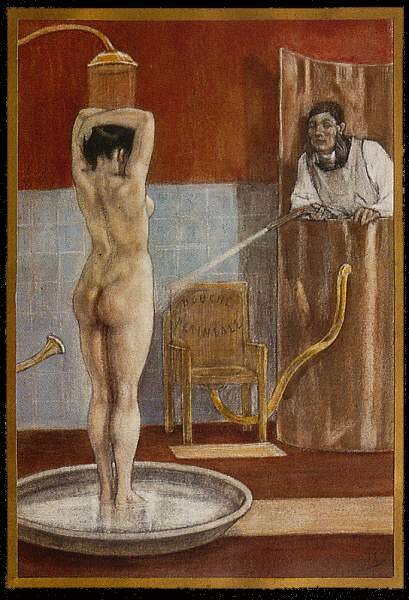

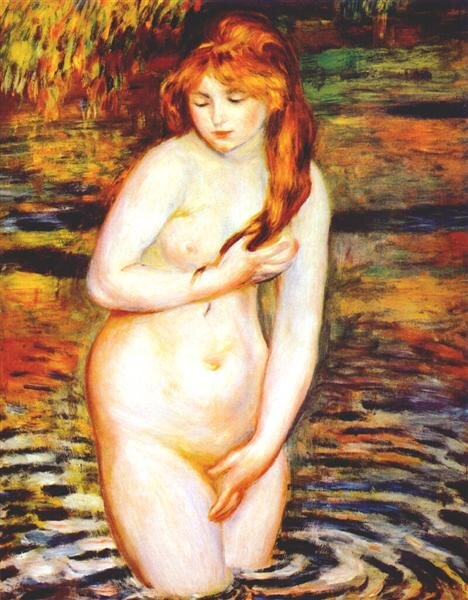

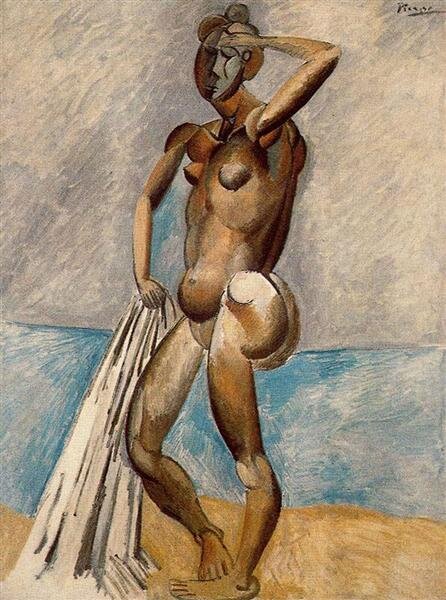

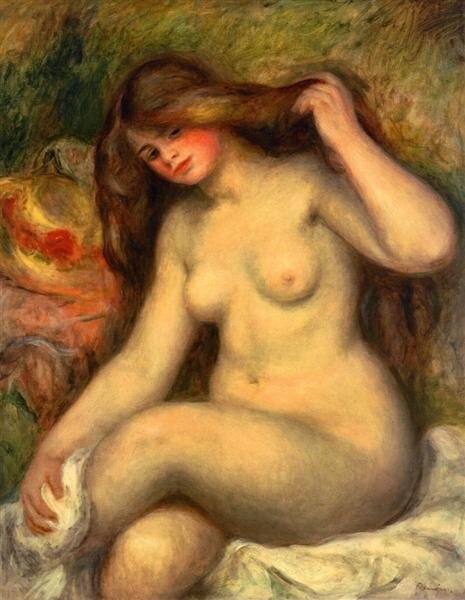

women bathing

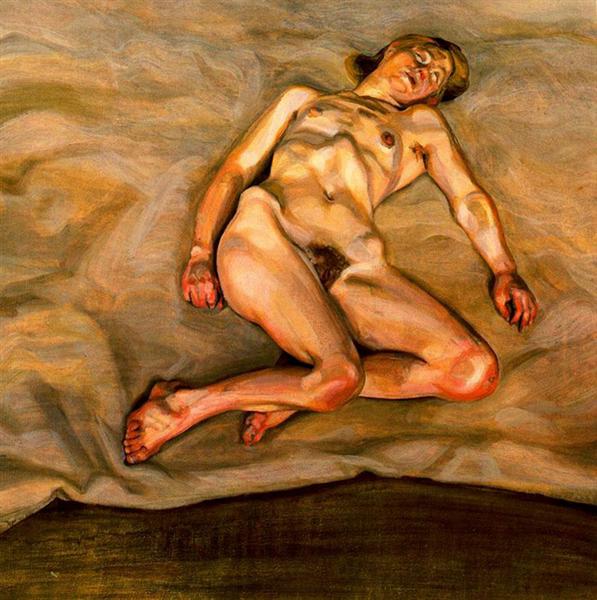

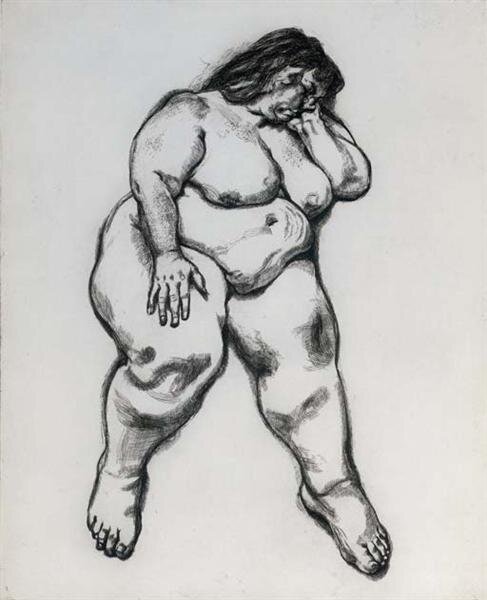

This obsession with women bathing in the art world continues on to focus on unnamed subjects… Who the woman is really does not matter at all, it seems.

Canadian painter, Alex Coleville brilliantly captures the sinister aspect of watching a woman bathing in this magnificent painting at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

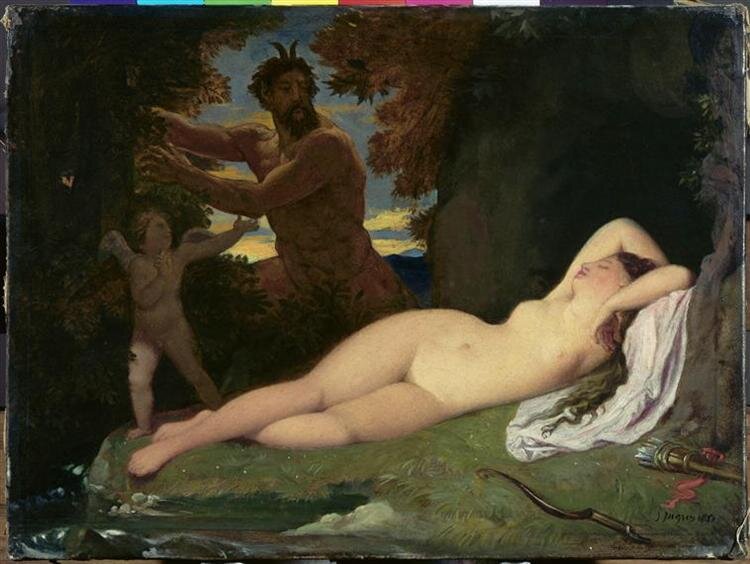

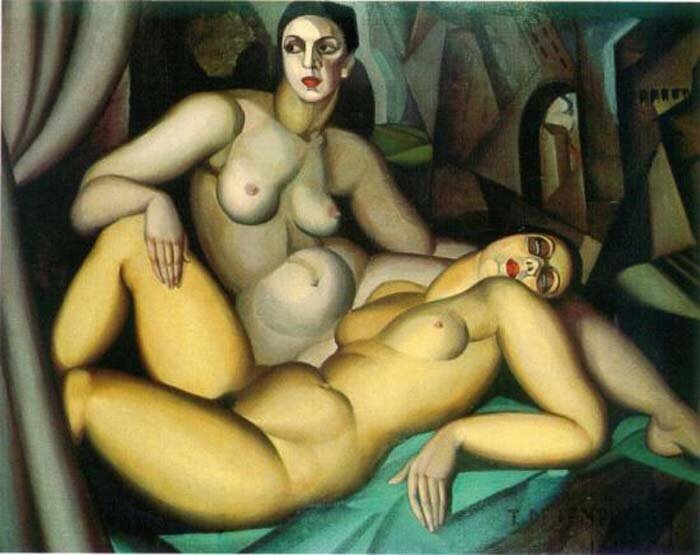

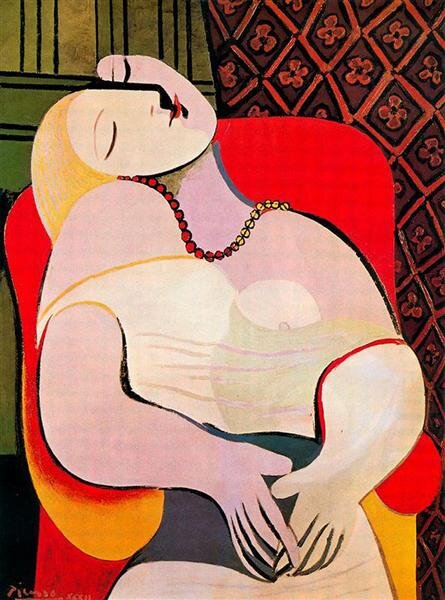

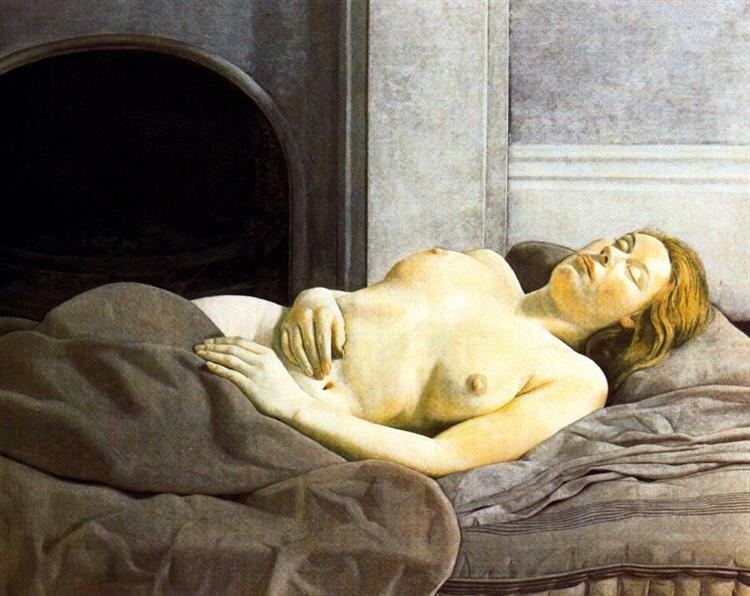

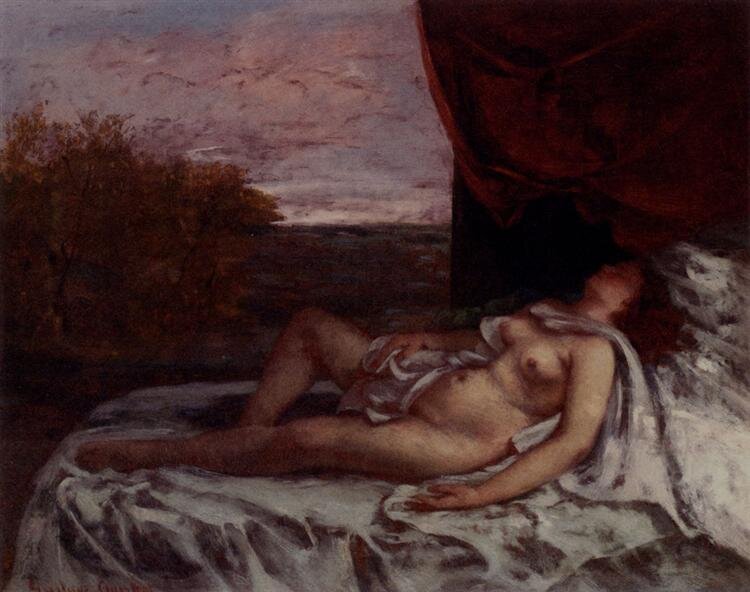

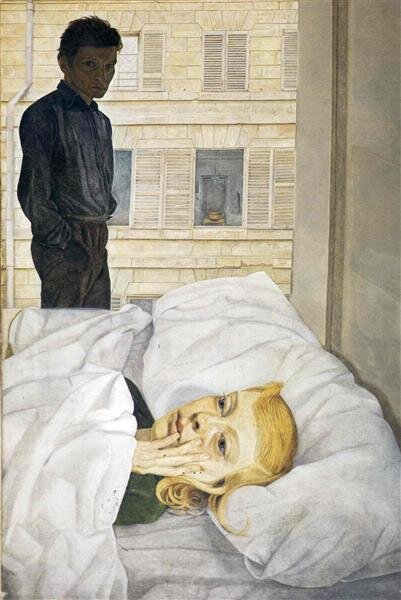

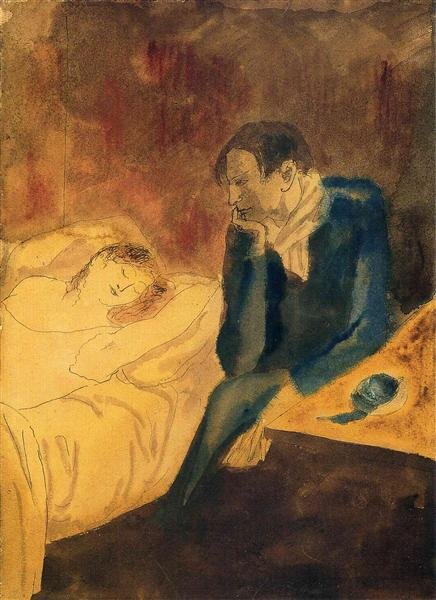

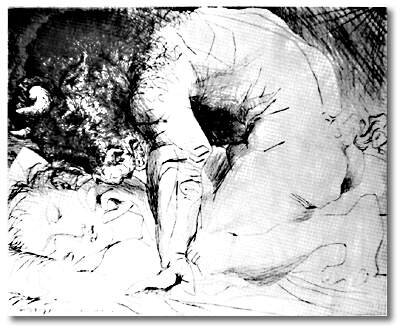

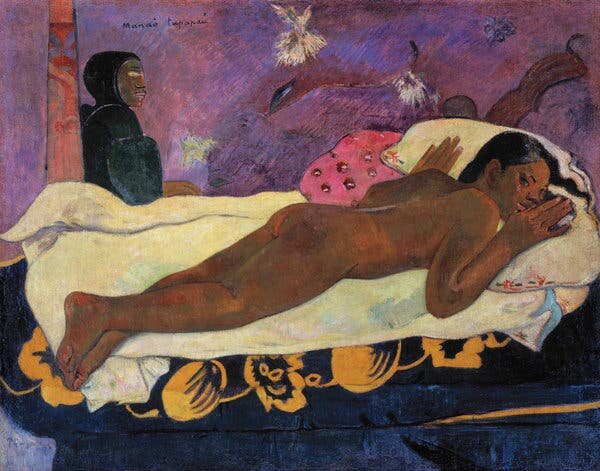

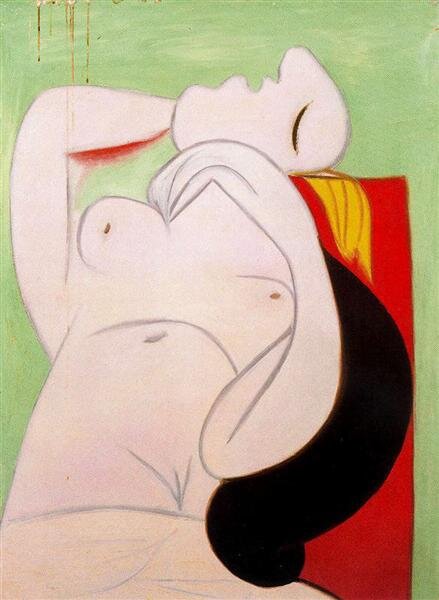

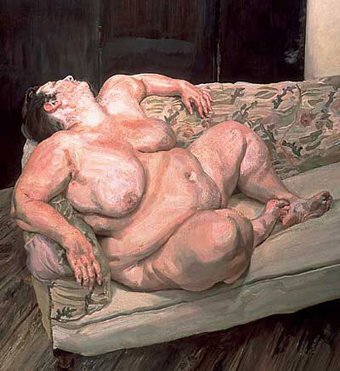

watching women sleeping

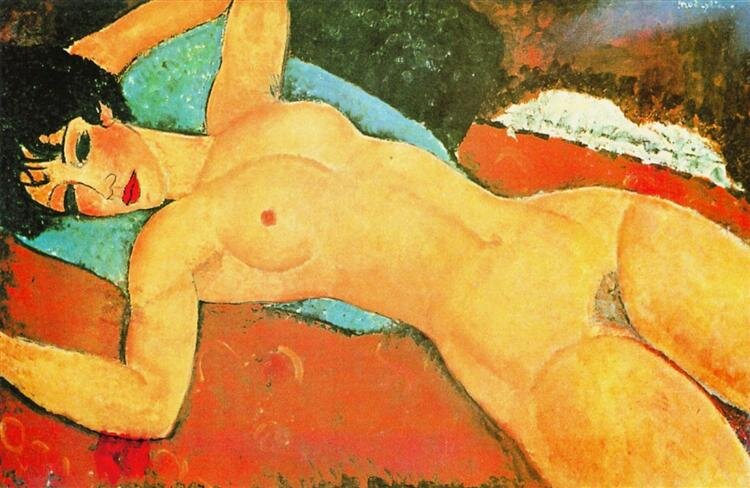

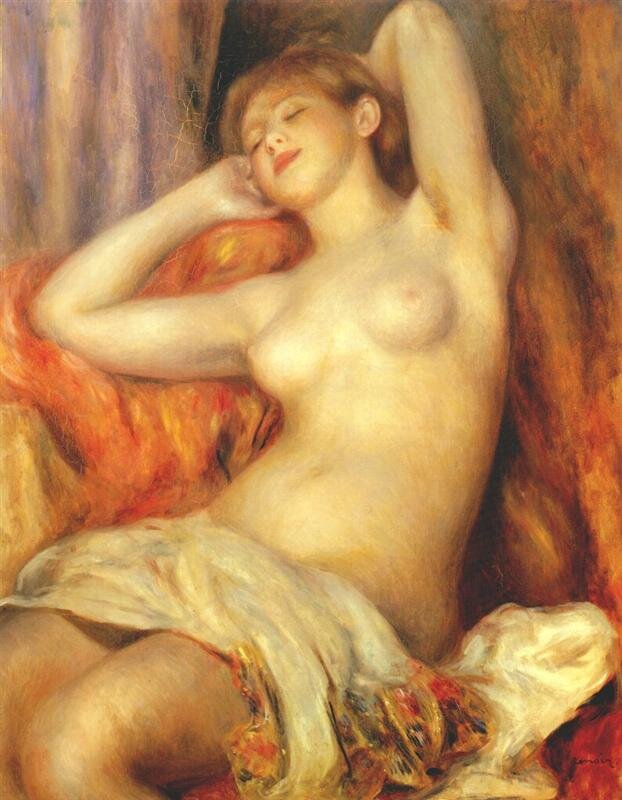

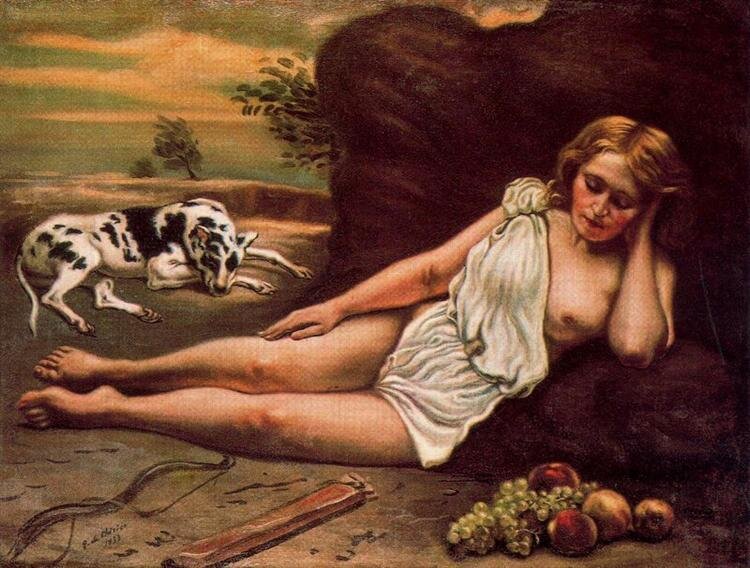

Venus sleeping

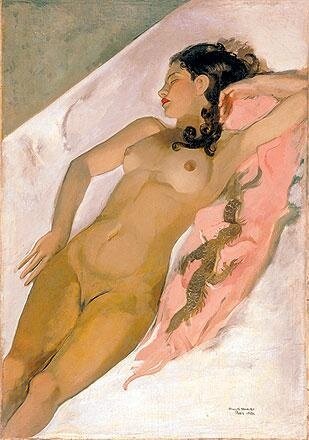

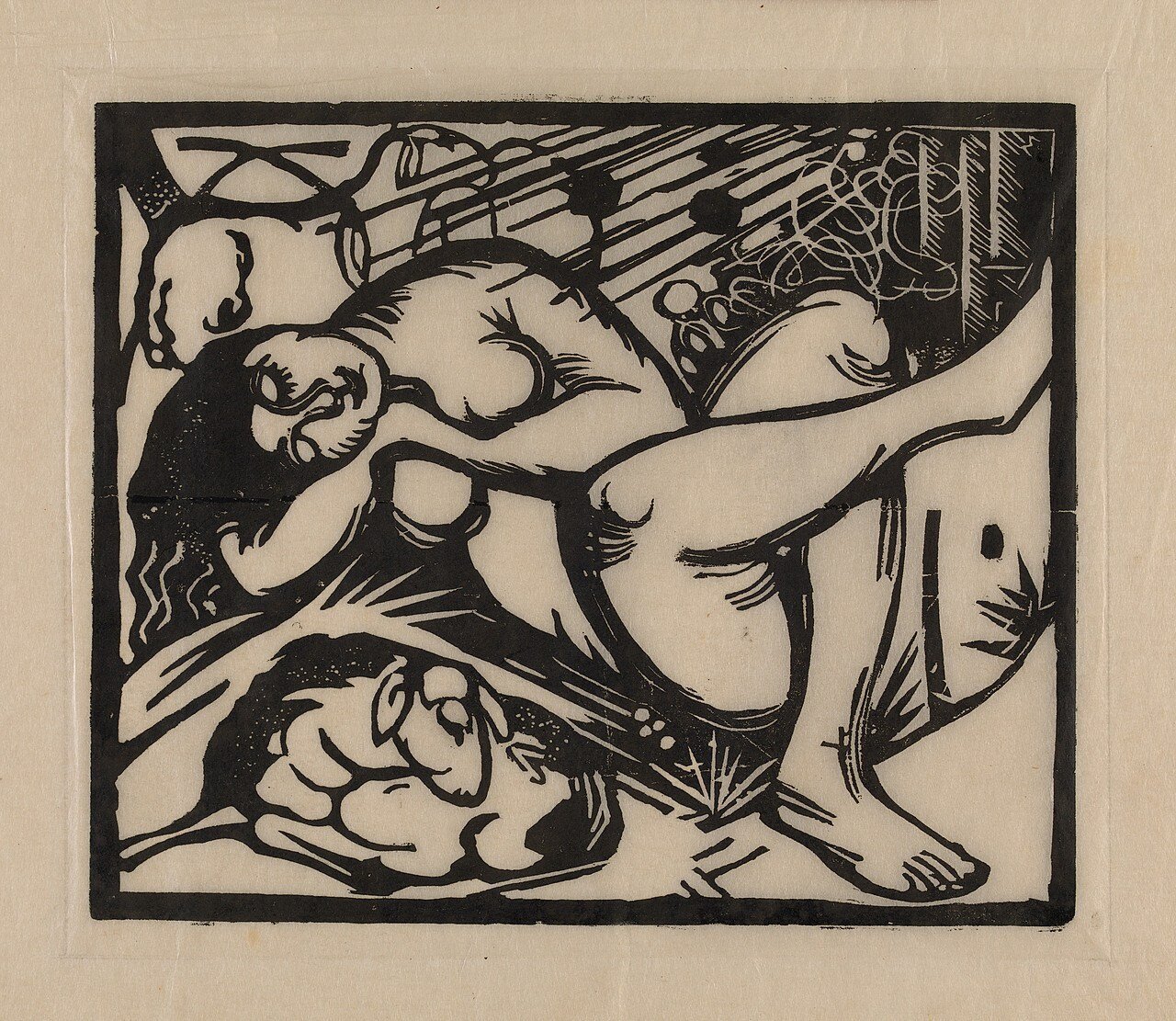

antiope sleeping

woman sleeping

Many of these images are sinister and threatening. The idea of someone watching us while we are sleeping is rarely a reassuring one, unless perhaps we are children. Would it be worth considering what ideas and feelings images such as these convey to the viewer? Is there a reason we wish to enable voyeurism without discussing the implications of such an act?