About Parallel Lines

The title Parallel Lines refers to the physical and emotional bars of the prisons in which we periodically find ourselves.

It also refers to how opposite sides of a road, in one-point perspective, appear to converge in the distance — just as seemingly opposing view-points can converge with a new understanding.

Parallel Lines began as a personal meditation on our tendency to imprison ourselves and others through our beliefs and choices.

It is also a reflection on the precarious journey that we all must take in order for us to escape our self-imposed prisons and find healing in our own lives and communities.

it all started . . .

In the 1980’s, I was working with the Canadian Association in Solidarity with Native Peoples.

I met a youth, Jimmy, who told me that by age sixteen he had lived in fourteen foster homes; and one day, deeply depressed, figuring no one wanted him — he threw a shovel through a jeweller’s window convinced — at least he’d be wanted in jail.

I met him at an Elder’s Conference, rebuilding his life, recovering from physical and emotional abuse, battling alcohol, drugs and systemic racism.

Jimmy recognized that his perspective on life and consequent beliefs had led him to take a decision that was not in his own best interests.

His story stayed with me.

I began to learn more about the history of First Nations people in Canada.

I was stunned how few people seemed to connect with what has been going on in this country.

I wondered: what does one need to do to make people care?

Years later — wrestling with my own issues: alienation, depression; racism, sexism; and the shame and guilt resulting from emotional abuse and sexual assault — I was contemplating suicide.

One day, I was crushing chicken wire in my bare hands to release the pain. I looked down and, aside from my bleeding hands, I saw that what I had created was actually beautiful.

It was a nest-like form, twisted and torqued.

I remembered a part of me that I hadn't known in a very long time.

I painted the wire black and mounted it on a panel painted in burgundy shades with two beige stripes.

A week or so later, a woman came to visit. She stared at the work and exclaimed:

"Oh my god! That's David!"

Her husband had recently killed himself.

Suddenly I felt heard. Seen.

I said nothing to her about my own issues but I realized I had a voice that people could finally hear and feel.

I began to heal when I realized that I — like Jimmy — had effectively created a prison for myself based on my own beliefs and constricted ideas of how life should be.

The choices we make are governed by a subjective perception of reality.

When we are prisoners of our own beliefs, we create prisons for ourselves and for others.

I found the keys to my own release — through the arts.

15 Minutes of Fame

In 2004 I was commissioned to create works with materials recycled from government buildings.

By this point in my life I'd spent many years creating enormous interactive sound sculpture installations from reclaimed materials. (see Arising Phoenix, Glove Forest, Dragon Tango)

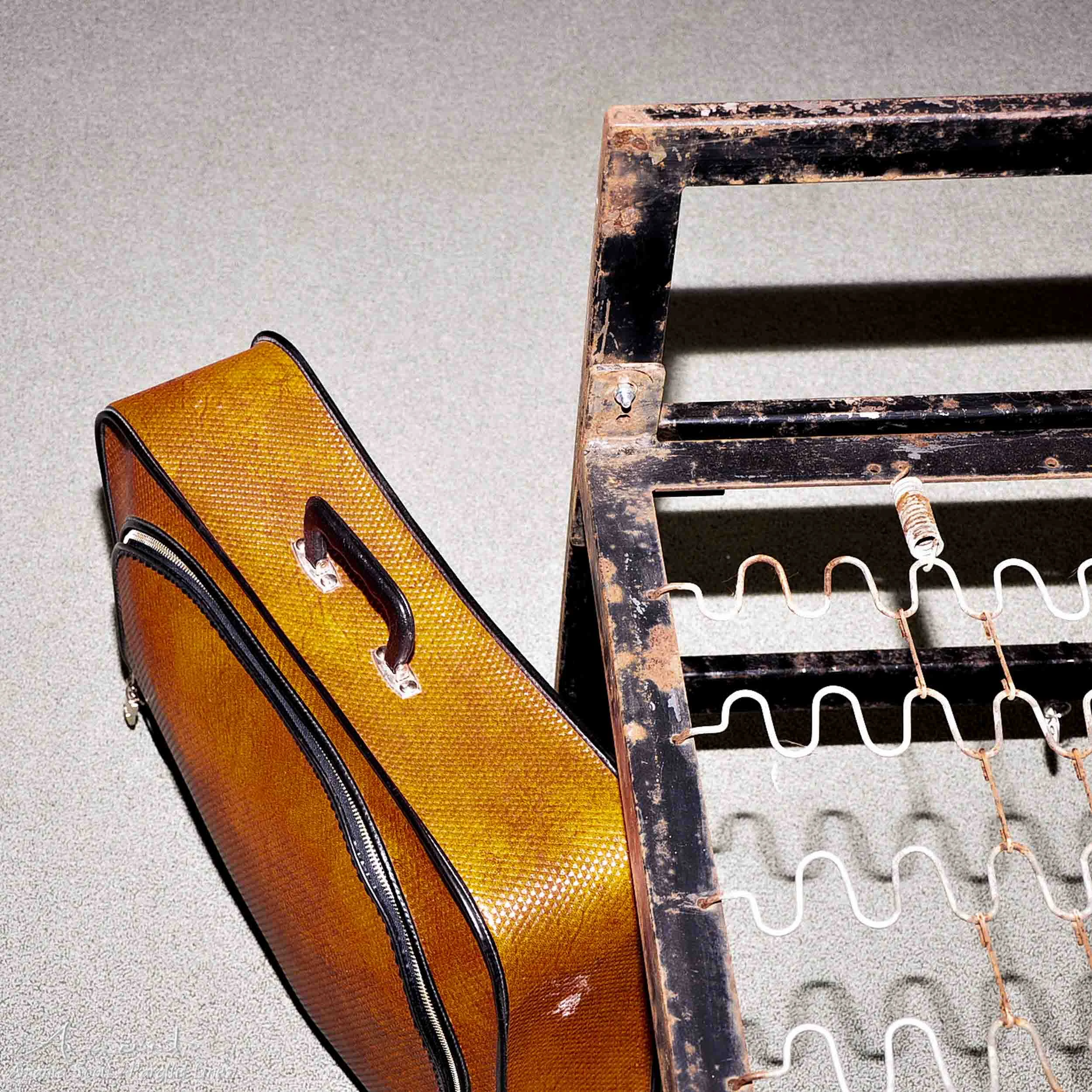

Correctional Services Canada asked if I might do anything with prison beds recovered from the former Kingston Penitentiary for Women.

Thinking of Jimmy, I created the interactive sculpture installation — 15 Minutes of Fame — to explore perception and choice — and conceived Parallel Lines.

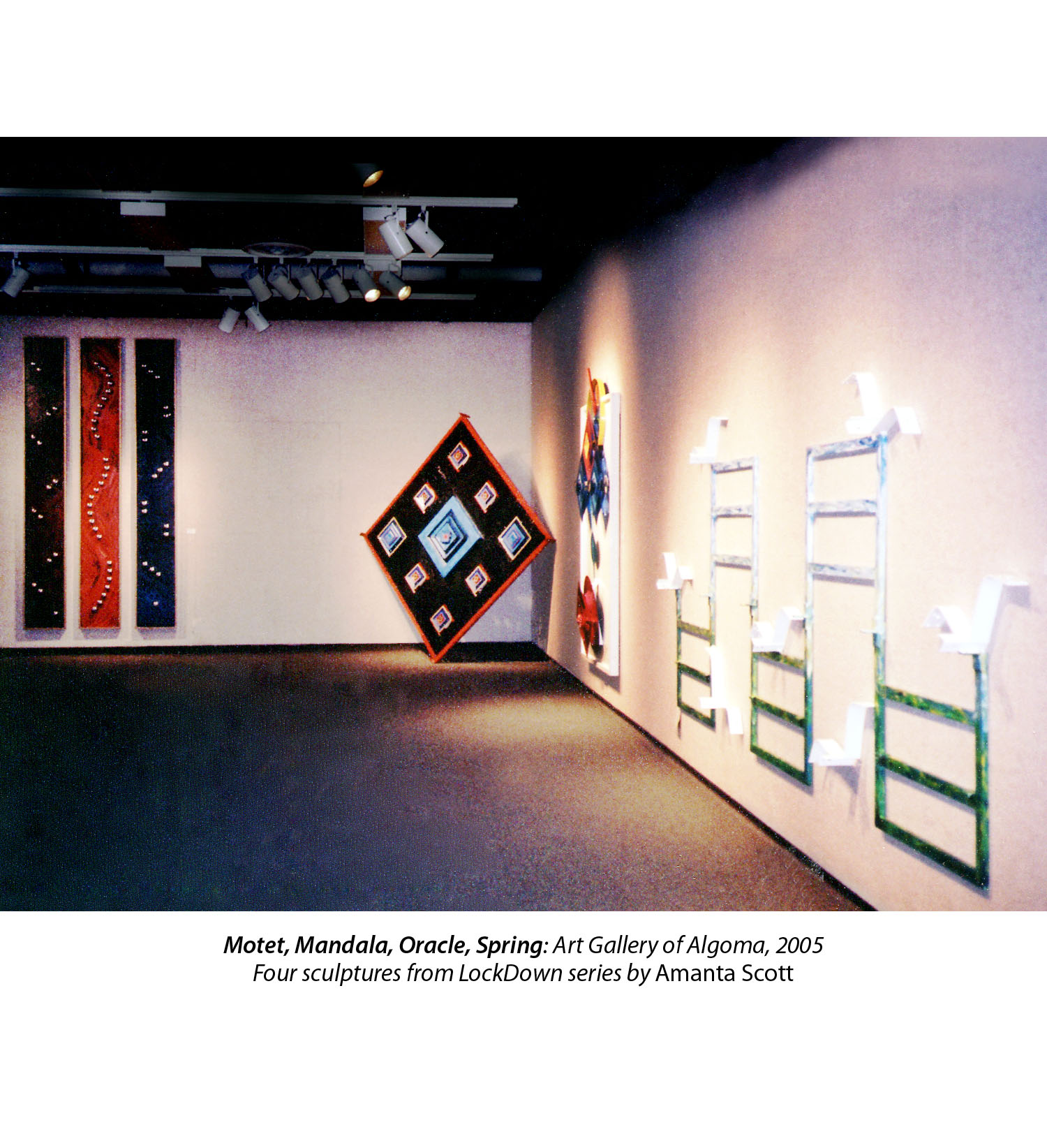

Correctional Services Canada gave me approximately thirty prison beds — from the now closed, former Kingston Penitentiary for Women, an institution itself loaded with history — with which I created the sculpture series LockDown which featured at Art Gallery of Algoma in 2004.

They also gave me the orange, standard-issue, get-out-of-jail suitcase which inspired the interactive installation 15 Minutes of Fame — featured in Parallel Lines.

At its first exhibition — Art Gallery of Algoma, 2004, I set about to bring new audiences into the gallery: people who wouldn’t normally be there — women from shelters; youth from halfway houses; former inmates; police; prison guards; social workers — with school groups and the general public to interact with the installation and participate in arts workshops.

Amongst this group were four youths from a half-way house program: troubled, functionally illiterate, and pushing boundaries from start to finish.

None of them had set foot in a gallery before.

A week later, one of them returned: demanding to “do the installation again” (15 Minutes of Fame) — significantly to include a personal photo in the empty picture frame found in the suitcase.

The experience had inspired him to invest himself in a work of art.

I knew I was onto something.

perceptions

With my mind reeling from stories told me by visitors the exhibition of 15 Minutes of Fame at Art Gallery of Algoma, I hired a photographer, John Davidson, to shoot a series of 'happenings' featuring me with the prison bed and suitcase in a variety of locations around Toronto.

I told him I was going to paint over the photos with encaustic paint.

John looked at me strangely and said —

"I'm a professional, you won't need to do anything to the photos"

I laughed and replied —

"A photo depicts what we all generally agree is reality.

In painting over them I impose my subjective version of reality over yours — much as we all do in life!"

And thus began the painting series — Perceptions

The paintings are not strictly autobiographical. Although I feature in each of the paintings I do not consider them self portraits in the truest sense.

When the photos were shot, I imagined myself in the place of any one whose stories I had been told, and put myself into what I imagined was their reality.

Initially I used myself as a model in the photos largely because I was on hand at the time.

However, as the paintings evolved I found myself over-painting the original photos, violating, distorting and often completely altering the original context and perspective in which they were shot to create an entirely different reality — in response to events unfolding in my own life and to the people around me.

With the start of the #MeToo movement and resultant discussions I have openly come to admit that there is an autobiographical component in this work.

More importantly, however, I hope the work speaks to what unites us as humans, touching upon the universality of experience.

In Memoriam

This installation was created in response to Visitors' observations that the prison bed in the paintings and in the first installation, 15 Minutes of Fame, reminded them of the beds they had encountered in residential and boarding schools, refugee holding centres, prisons and shelters.

The beds have triggered a range of emotions, memories and stories from Visitors.

A friend suggested that the work might be useful in helping people heal, particularly in the truth and reconciliation process regarding what has been done to First Nations people through the residential school system and the sixties scoop.

I really hope this will be possible. The beds have certainly triggered memories and assisted in the emotional release and healing of people of other cultures.

At the premiere exhibition of In Memoriam — Museum of Northern History — a Visitor asked me if she could sit down on one of the beds. Of course, I said, yes.

Once seated, she immediately burst into tears. She then told me a story of her parents coming from Ecuador. She said she had been carrying the burden of their trauma for years and feared she would pass it on to her children.

We spoke for a while and I directed her to a crisis counsellor from Canadian Mental Health Association who had partnered with me for precisely this reason.

I spoke with the Visitor again afterwards and she told me that for her the entire experience had been cathartic.

Fragile

There is an expression in English — walking on eggshells — which is used to indicate something that must be approached very delicately and with caution.

The path each of us must find and consequently walk on our own journey of healing is one that must be navigated with similar care. We are fragile beings.

For me, the work also speaks to the history of my ancestors and those of my dearest friends: family members murdered in the streets, missing, evacuated with less than ten minutes notice to flee their homes; the journey of refugees and immigrants.

The idea for this installation originated in 2011 with my interdisciplinary performance Shellshock, which focused on our ability to pick up the pieces, rebuild our lives and learn to love again — even in the face of unspeakable trauma, horror and disaster.

However, it was during the planning of Parallel Lines, when I ran up against people's fear, racism, guilt and self-hatred that I began to see how relevant the concept of walking on eggshells could be in a new context: as a performative process-oriented work in which the Visitor becomes the performer and participant.

This led to the final work in this project: Esperanza.

Esperanza

This interactive sculpture installation premiered at Museum of Northern History, Kirkland Lake, 2018.

Where there is a prison there must be a key to lock or release the door.

Sometimes the hardest thing for us to do is to forgive ourselves for what we have done; as well as for what has been done to us.

Each of us needs to find the key that allows us to release ourselves from our self imposed prisons and move on.

Esperanza features a prison bed (suspended from the ceiling on the diagonal or standing on end if so required). The bed is adorned with spare keys attached to manila tags upon which Visitors have written one word indicating what it is they seek in life to release them from their personal prisons.

in conclusion . . .

Together, the paintings and interactive installations become an outreach project in which the viewer plays an integral role. Viewers share their impressions and stories that the works brings to their minds, often enacting them before other onlookers — creating an ever-shifting narrative of imprisonment, freedom, isolation, community, self-sufficiency, dependence, desperation, and hope.

Viewers bring their own ‘baggage’ to the work mentally or physically when they sift through the contents of the suitcase or project their own histories and perceptions atop the paintings, much as I applied the pigmented beeswax onto and beyond the underlying photo.

What, hence, is ‘real’ or original, what manufactured and ‘imagined’? The lines blur . . . or are, in fact, parallel: we can never fully step out from behind the bars of our own perceptions.

Parallel Lines provokes, disturbs, questions, embracing the undetermined and the indefinite. But it is precisely this open-endedness that inspires debate and interaction across the barriers —cultural, economic, religious, linguistic, and political — that usually separate us. And from these debates and interactions spring possibilities and new perspectives.

Connecting and engaging with strangers through play, performance, laughter and conversation — empowers us and enables us to appreciate the values, priorities and perspectives of others.

Cultivating compassion and empathy in centres of colonial cultural power, Parallel Lines brings together: Canadians; First Nations people; Newcomers; refugees; former inmates; residential school survivors; abused women; insomniacs; recovering alcoholics; refugees; and travellers . . . to consider and discuss physical and emotional imprisonment; alienation; sexism; appropriation; misappropriation; and systemic racism.

Parallel Lines empowers people to voice intense, personal and political issues; deepen understanding; forge connections; and engage meaningfully with the arts.

CANADIAN HISTORY

For over 100 years Aboriginal children were removed from their families and sent to Residential Schools. The government-funded, church-run schools were located across Canada — established with the purpose to eliminate parental involvement in the spiritual, cultural and intellectual development of Aboriginal children.

The last school closed in the late 1990s.

More than 150,000 First Nations, Métis and Inuit children were forced to attend these schools — some of which were hundreds of miles from their homes. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has determined that the cumulative impact of residential schools is a legacy of unresolved trauma passed from generation to generationand has had a profound effect upon the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and other Canadians.

A disproportionate number of Aboriginal people are imprisoned in Canada. Aboriginal children account for a much larger part of the child welfare system's caseload than their share of the population. Both those trends are consequences of the residential school system.

The TRC found that people raised in the residential schools sometimes found it difficult to become loving parents. Those who were abused went on to abuse other people as adults or fell victim to substance abuse.

Students who were treated and punished like prisoners in the schools often graduated to real prisons. For many, the path from residential school to prison was a short one.

A small brown suitcase — packed with sacred medicines and a poem — was placed in the TRC's Bentwood Box by residential school survivor Marcel Petiquay, as a symbol for healing and reconciliation.

This suitcase represents the many suitcases packed by parents of the children, filled with ceremonial clothes, dried meats and beaded moccasins.

Most of the suitcases were immediately removed the moment the child got through the front doors — and returned empty, upon leaving.

I offer Parallel Lines — as a vehicle for healing and personal artistic expression.