Vitastjerna's dream from the Gutasaga with the three entwined snakes symbolizing Graip, Gute and Gunfjaun, with her at the bottom, Gotland, Sweden. Now in Fornsalen museum, Visby.

Gustav Klimt, 1900-1907, Klimt University of Vienna Ceiling Paintings. The bottom portion of the Medicine picture, showing Hygieia

Alexander Handyside Ritchie, College of Physicians, Queen Street, Edinburgh

image from Wikipedia

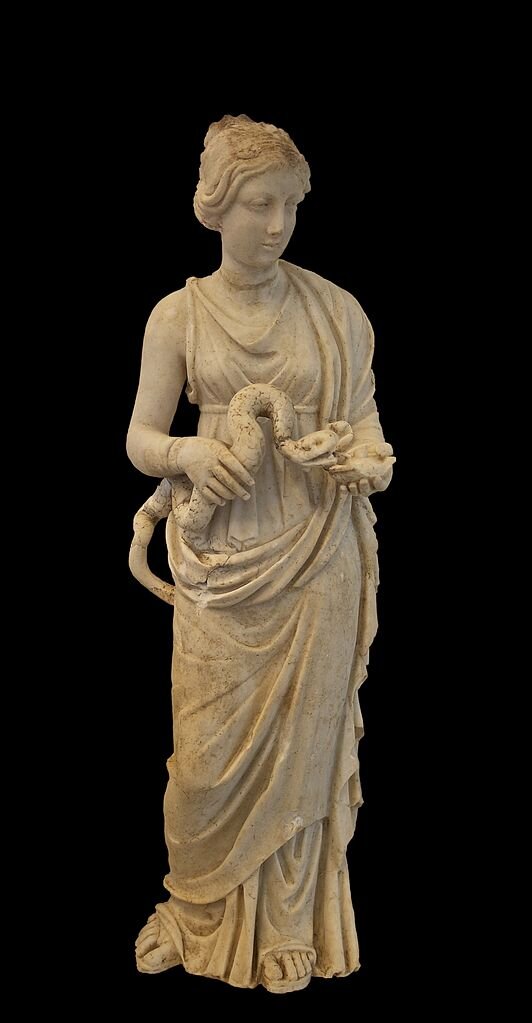

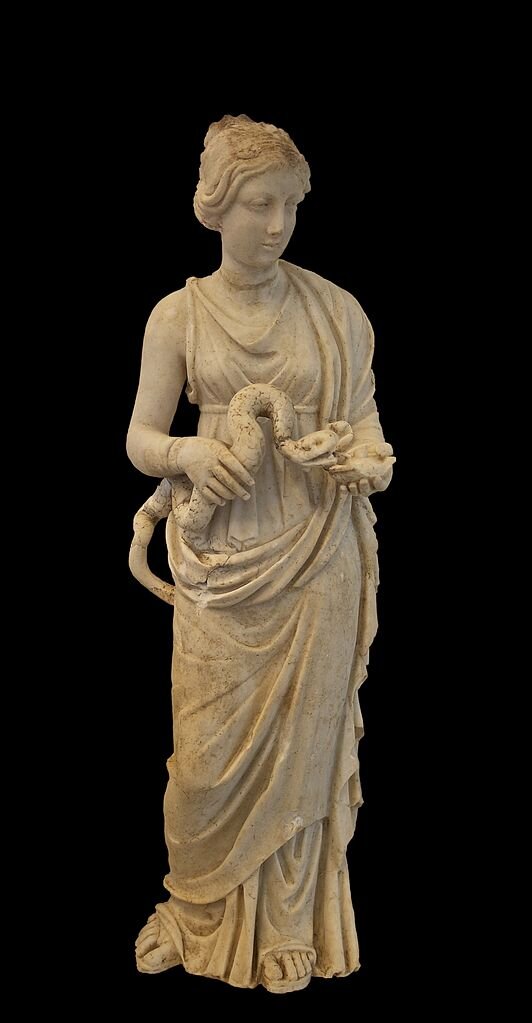

Small statue of Hygieia. Mid-2nd century C.E., Archaeological Museum of Rhodes

image from Wikipedia

Statue (head) of the goddess Hygieia, daughter of Asclepius, by the Greek sculptor Scopas (c. 395 BC – 350 BC). From the temple of Athena Alea at Tegea, exhibited at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

image from Wikipedia

Venus-Hygieia. Roman, made in Asia Minor, about A.D.200, Getty Villa

image from Wikipedia

Hygieia fountain in the city hall courtyard, Hamburg, Germany

image from Wikipedia, photo by Daniel Schwen

Hygieia fountain in the city hall courtyard, Hamburg, Germany

image from Wikipedia, photo by Daniel Schwen

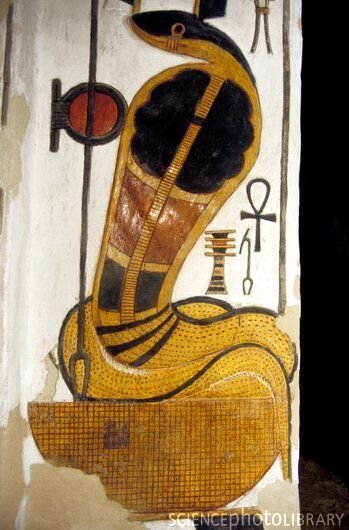

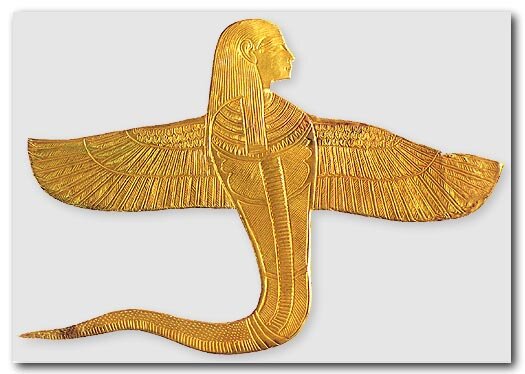

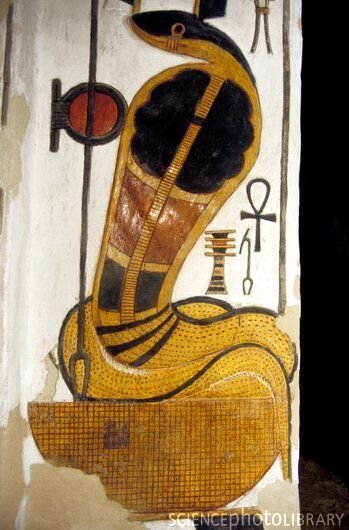

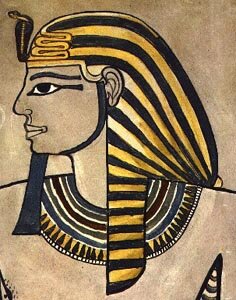

Buto, Cobra Goddess of Lower Egypt (also known as Ua Zit, Uatchit, Udjat, Wadjet, Wadjit, Edjo). She was portrayed as the Uranus cobra worn on the Pharaoh’s brow.

image from Egyptianmyths.net

(painting from the tomb of Nefertari, ca 1270 BC)

image from ferrebeekeeper.wordpress.com

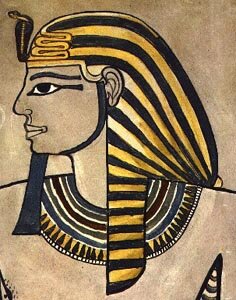

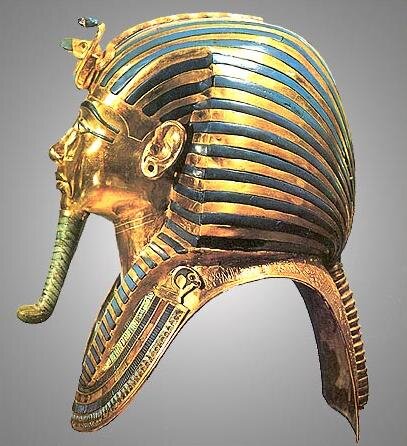

Amenhotep II wearing the Uraeus (painting, ca. 1400 BC)

image from ferrebeekeeper.wordpress.com

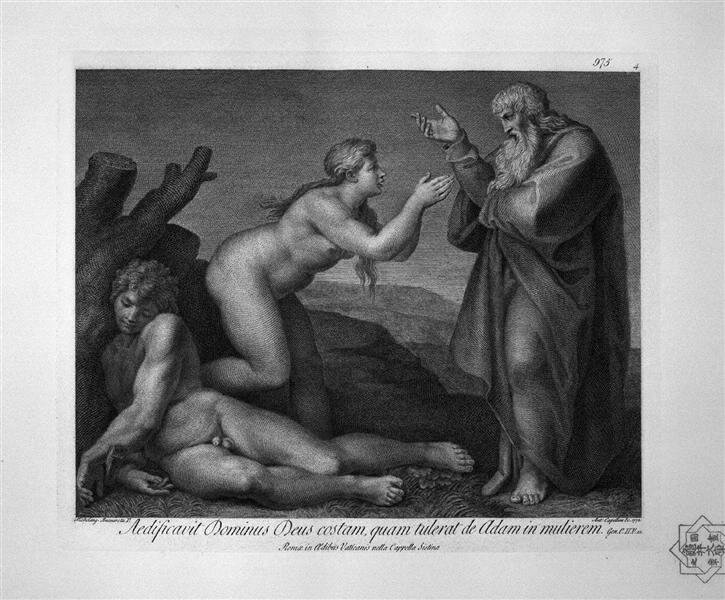

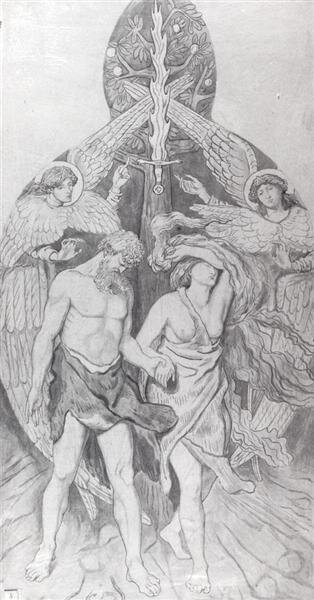

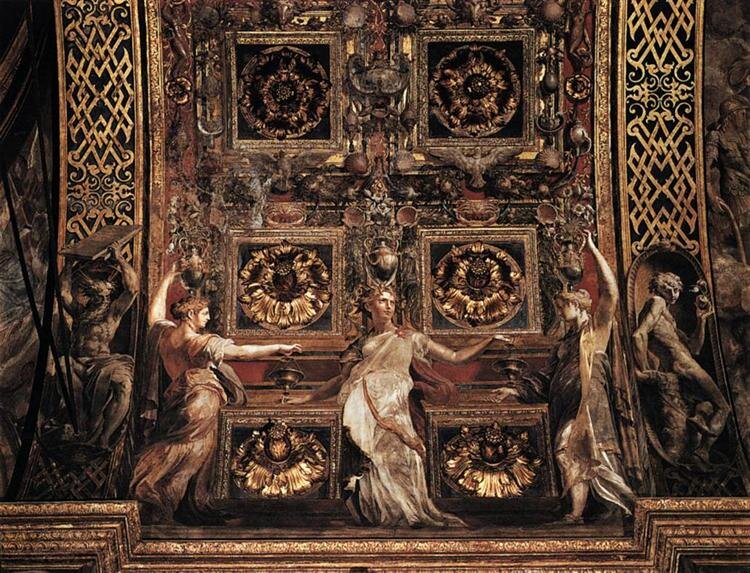

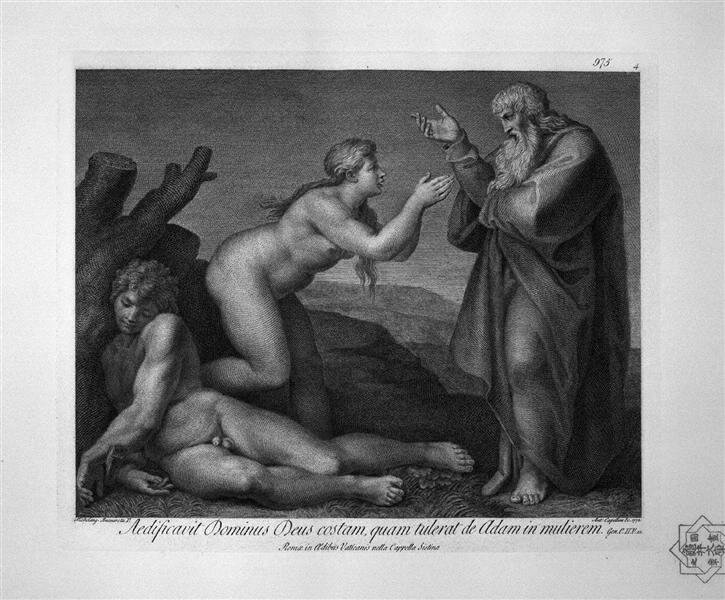

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Neoclassicism

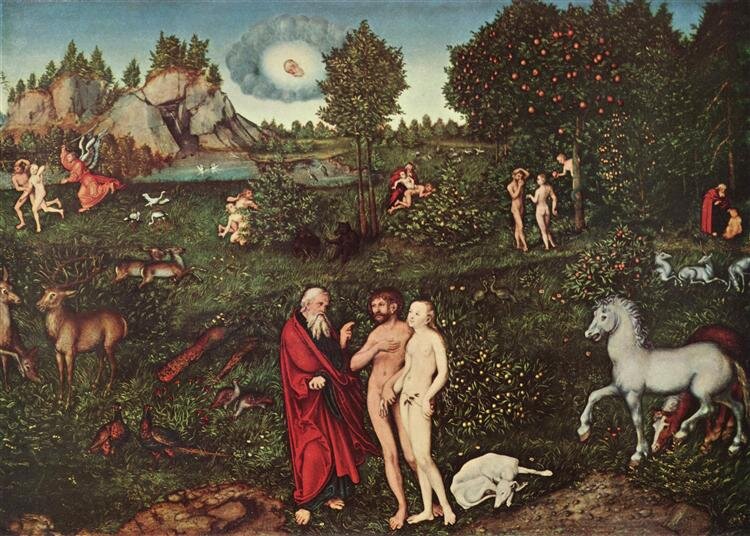

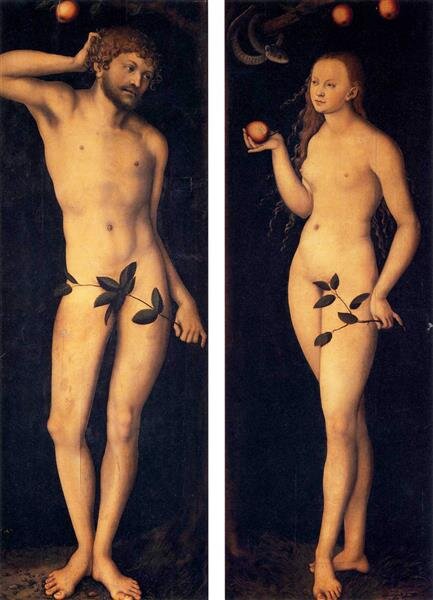

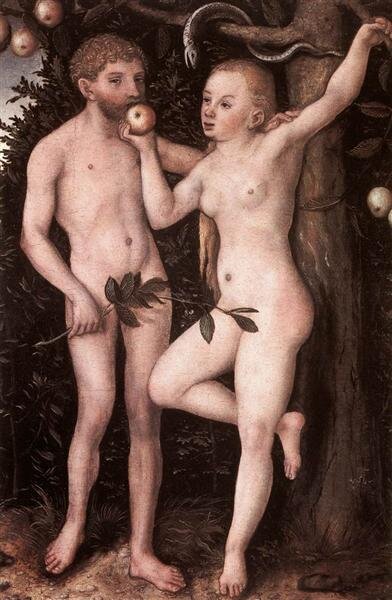

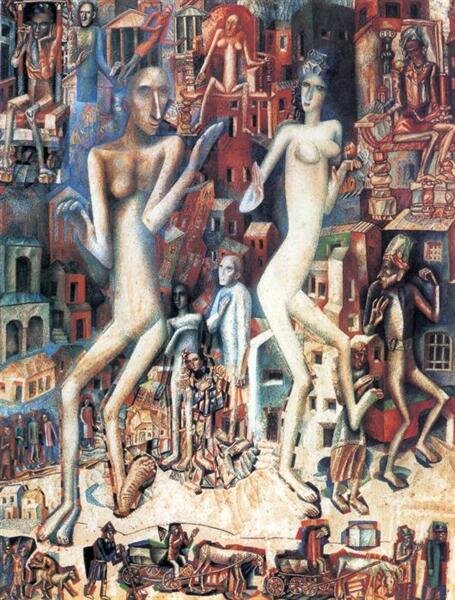

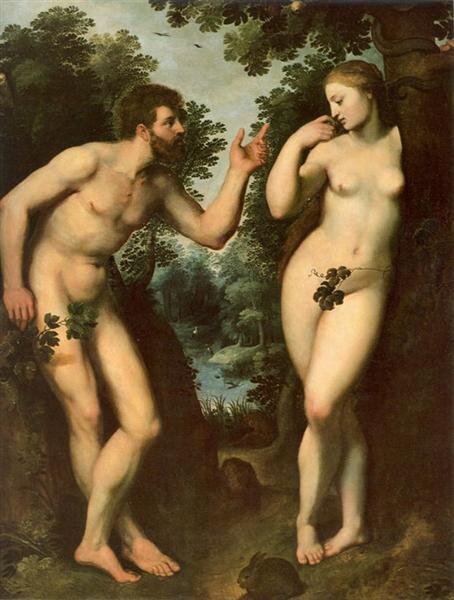

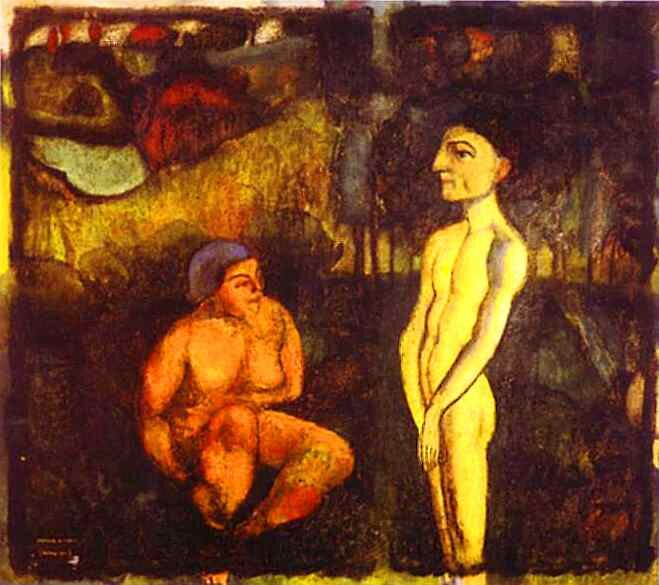

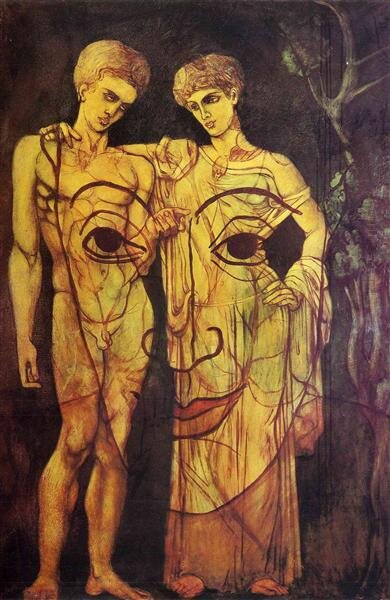

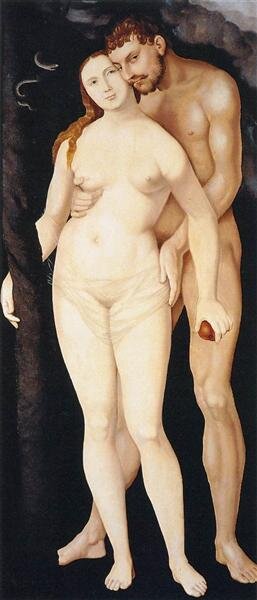

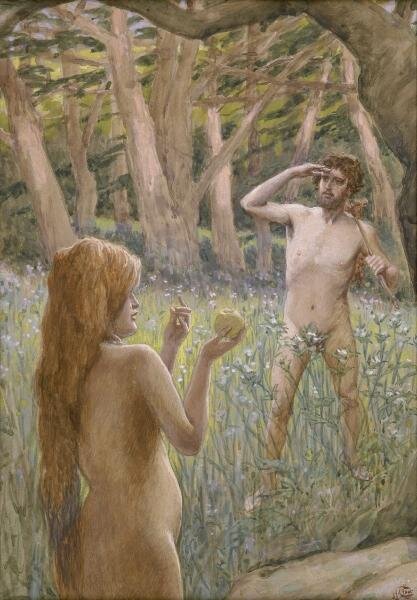

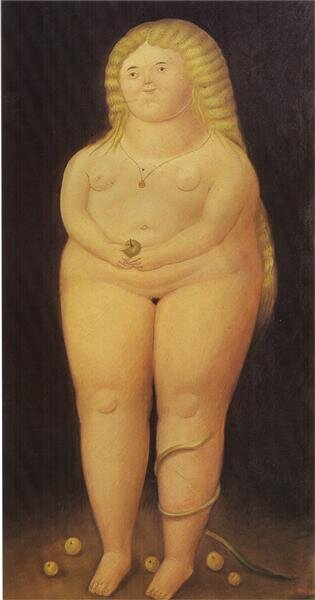

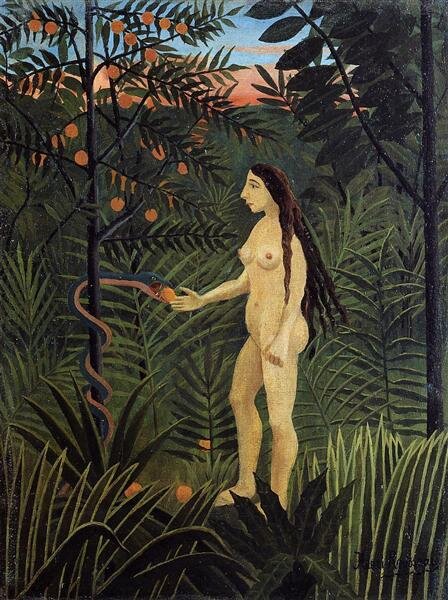

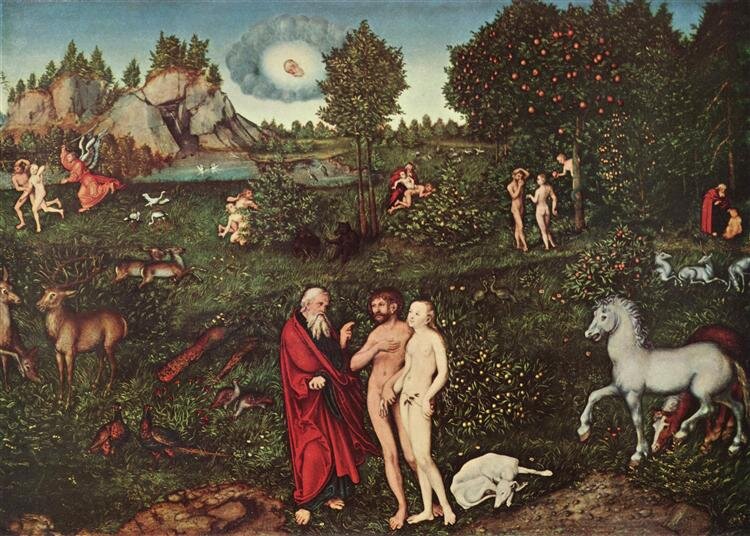

Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1530, Northern Renaissance: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

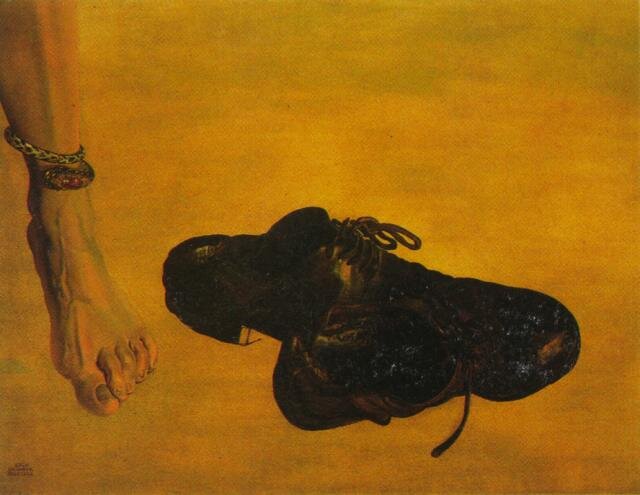

Fernand Leger, 1935 - 1939, Purism: Musee National Fernand Leger, Biot, France

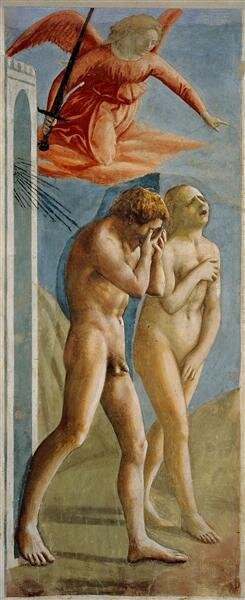

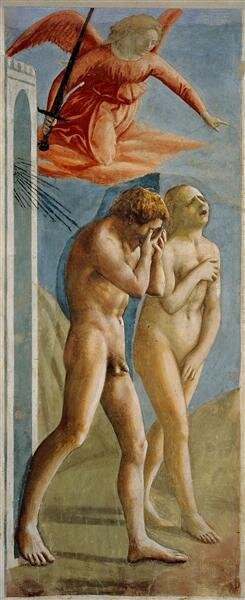

Masaccio, c.1427, Early Renaissance: Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, Italy

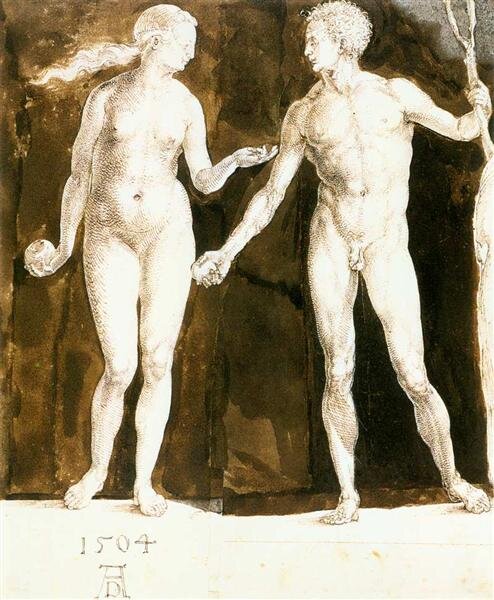

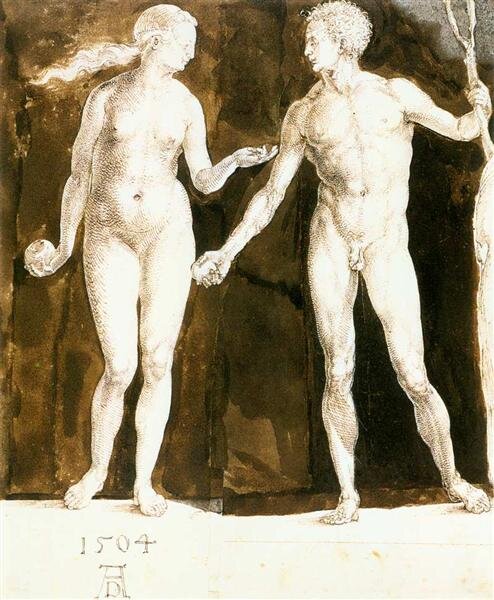

Albrecht Durer, 1504, Northern Renaissance: Morgan Library and Museum (Pierpont Morgan Library), New York City, NY, US

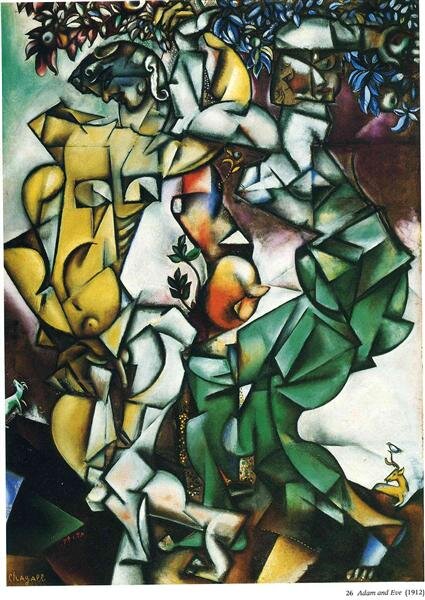

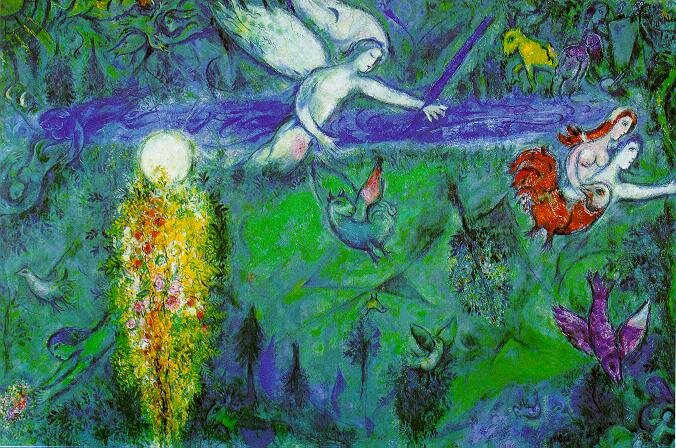

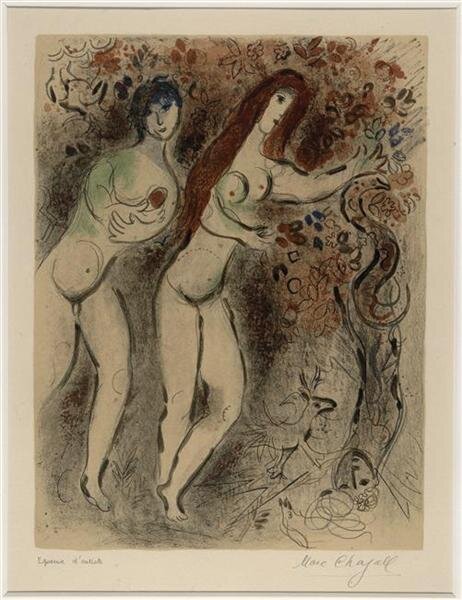

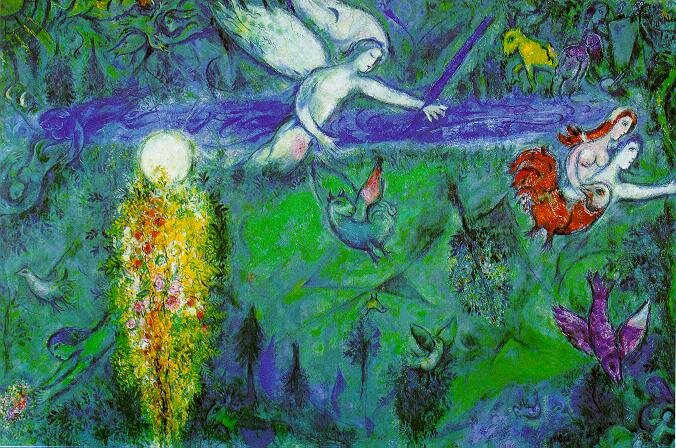

Marc Chagall, 1960; France, Naïve Art (Primitivism)

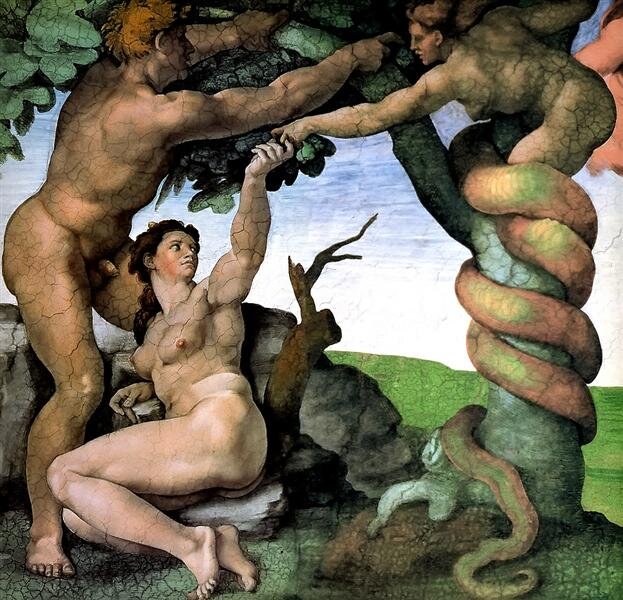

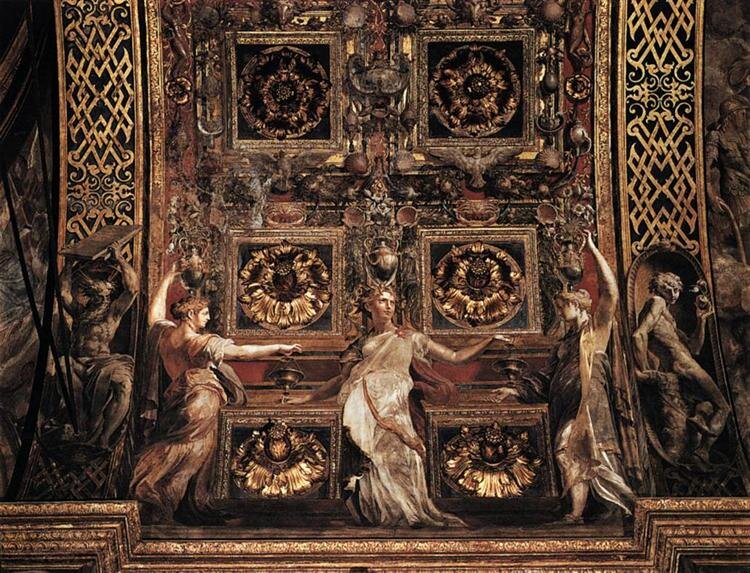

Parmigianino, c.1531 - c.1539, Mannerism (Late Renaissance): Sanctuary of Santa Maria della Steccata, Parma, Italy

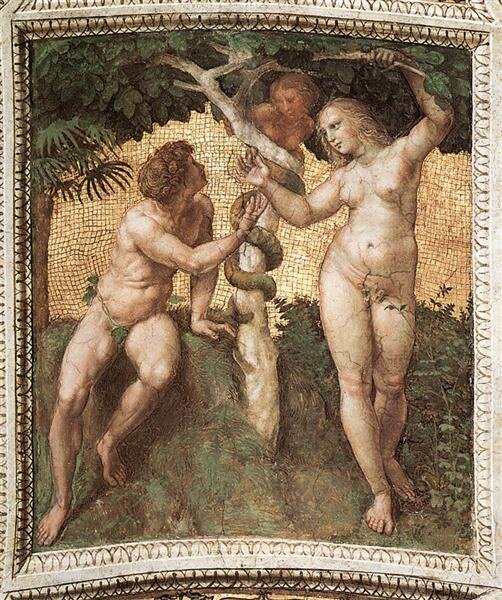

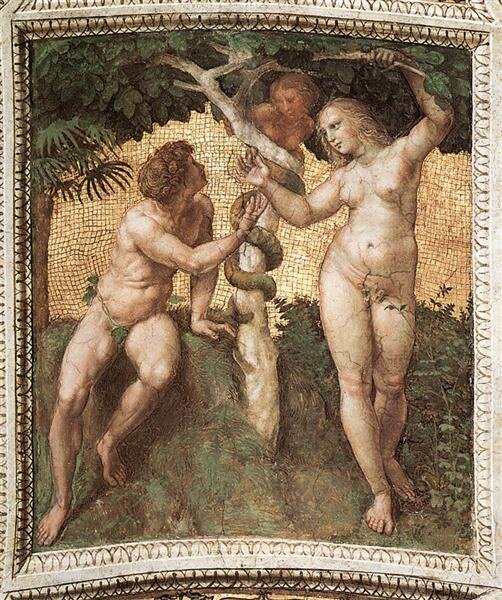

from the 'Stanza della Segnatura' Raphael, c.1508 - 1511, High Renaissance: Vatican Museums, Vatican

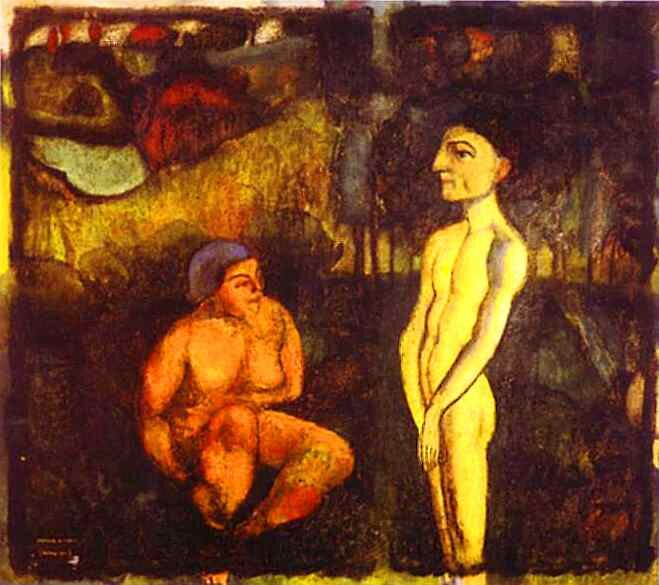

Marcel Duchamp, c.1910; France, Post-Impressionism: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA, US

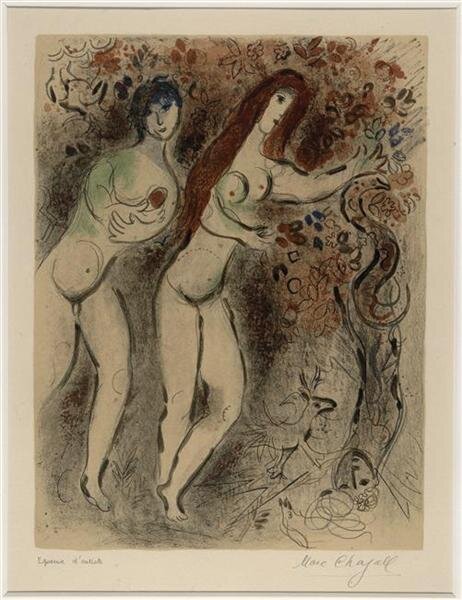

Marc Chagall, 1961; France, Surrealism

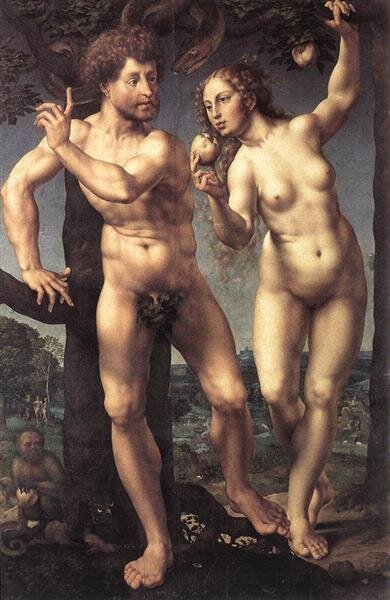

Adriaen van der Werff (1659–1722): Louvre Museum

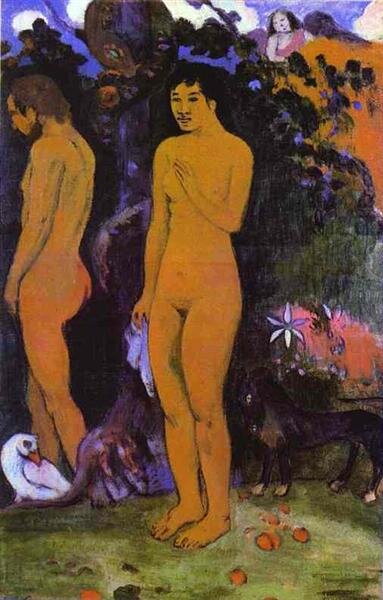

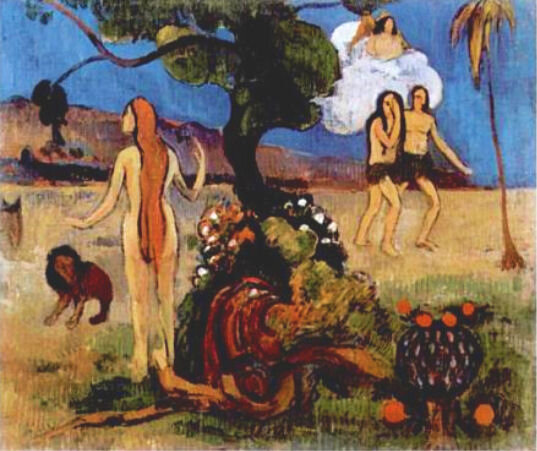

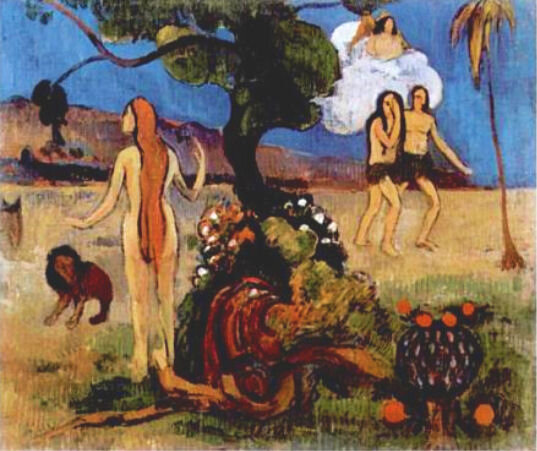

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903): Yale University Art Gallery (Inventory)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1868, Romanticism: Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE, US

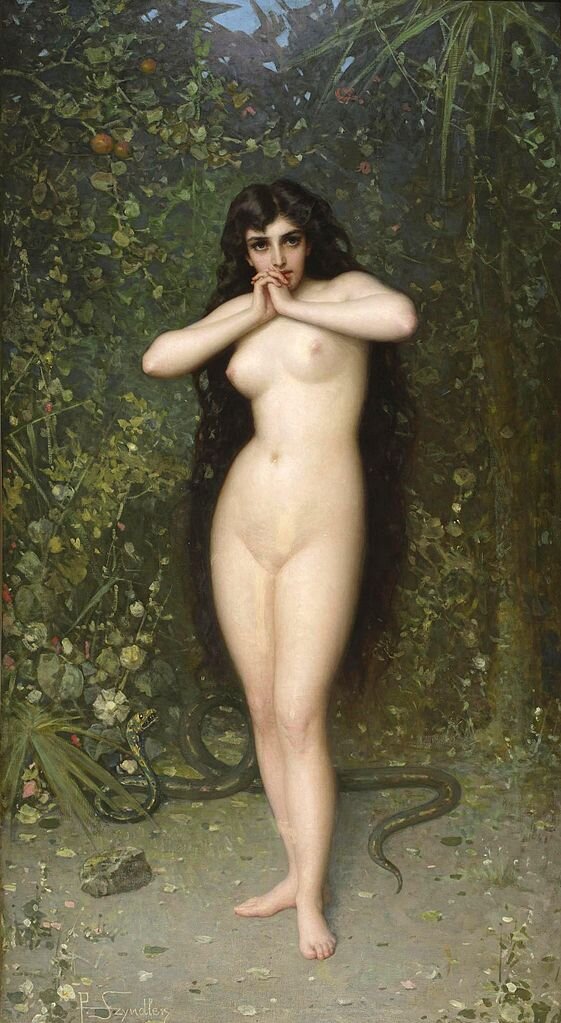

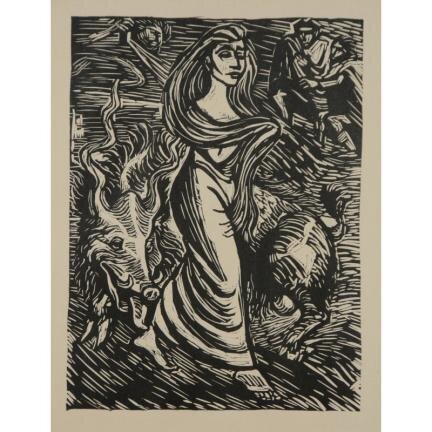

According to ancient Judaic myth, Lilith is "the first wife of Adam" and is associated with the seduction of men and the murder of children. She is shown as a "powerful and evil temptress" and as "an iconic, Amazon-like female with long, flowing hair."

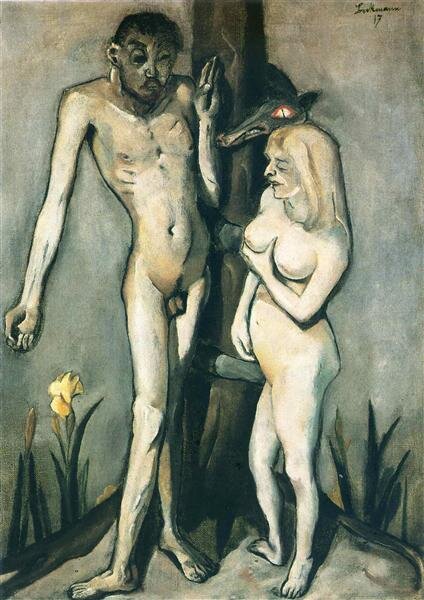

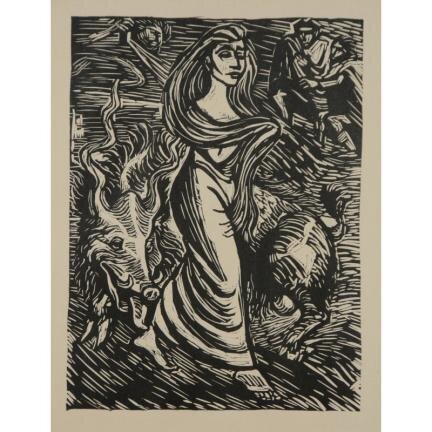

Lilith, Adam's First Wife, illustration from the poem Faust, from Goethe's Walpurgisnacht/ Walpurgis Night; Ernst Barlach: 1923, McMaster Museum of Art

Publisher: CASSIRER, Paul

Dimensions: Block: 19.2 x 14.3 cm (7 9/16 x 5 5/8 in.) Support: 31.4 x 23.2 cm (12 3/8 x 9 1/8 in.)

Medium: Woodcut on paper

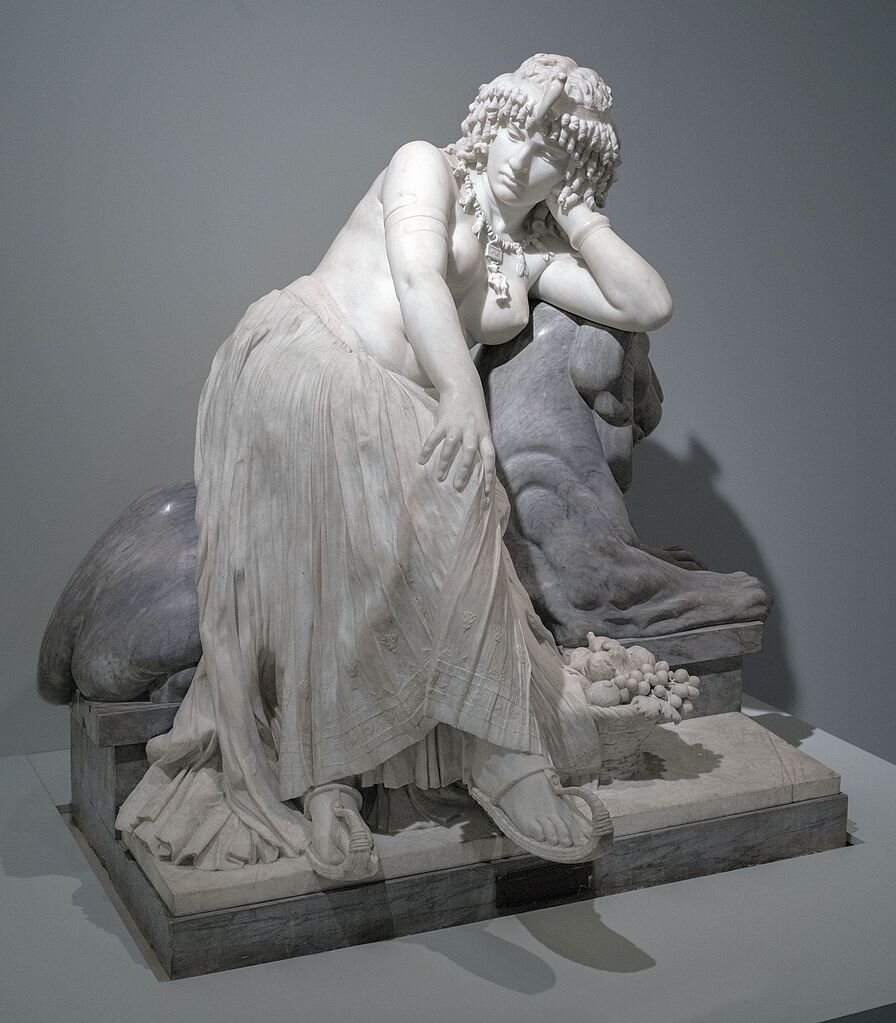

Edmonia Lewis, carved 1876, marble, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Historical Society of Forest Park, Illinois, 1994.17

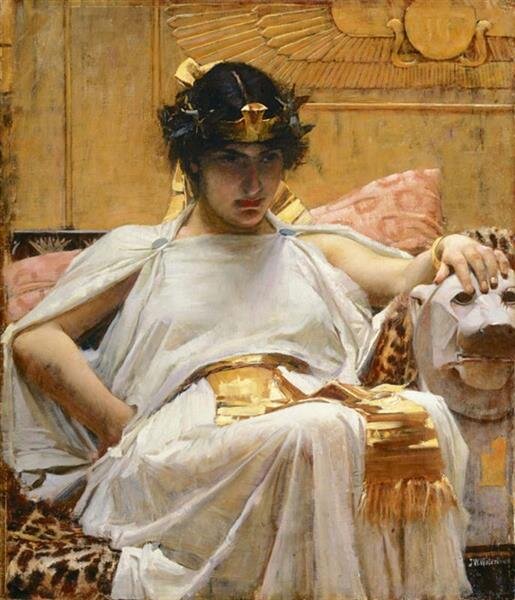

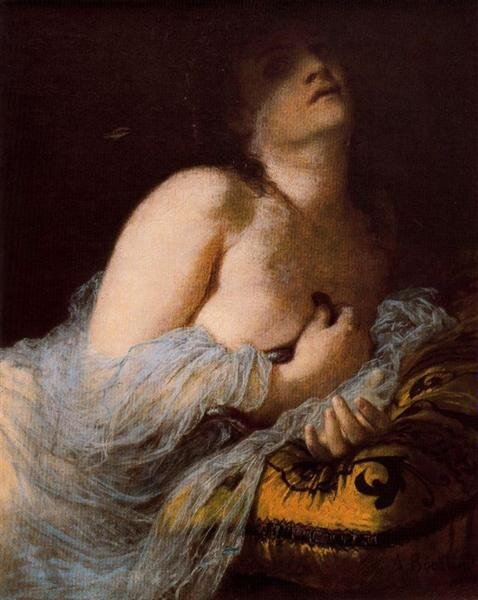

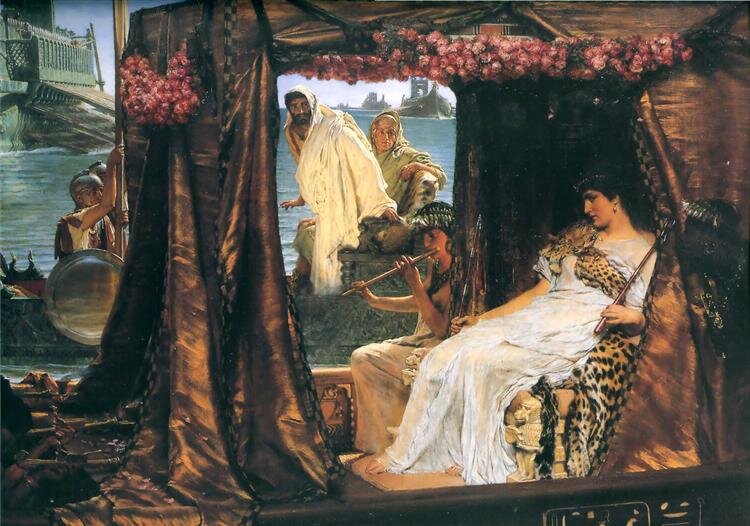

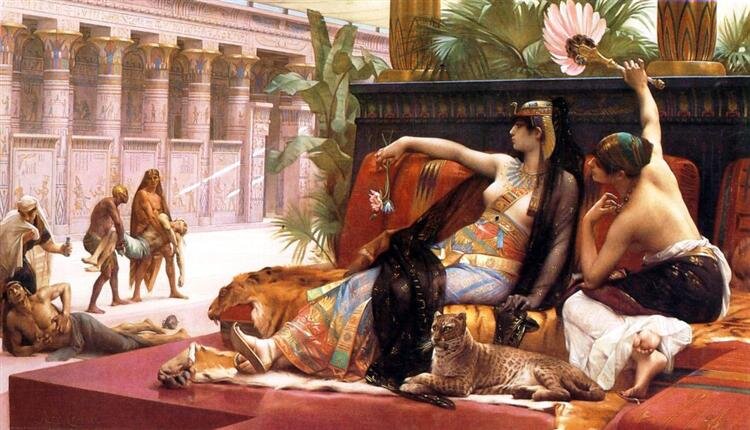

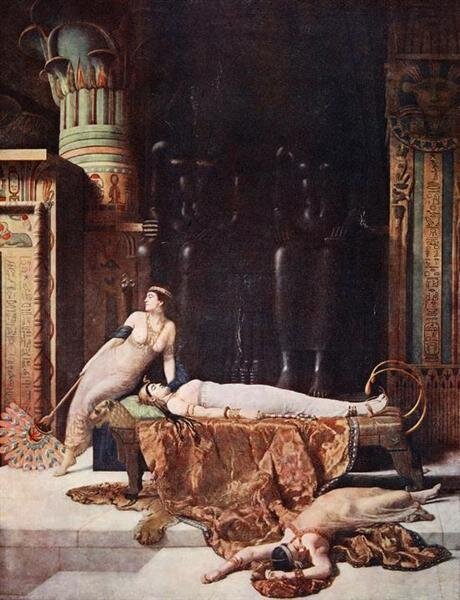

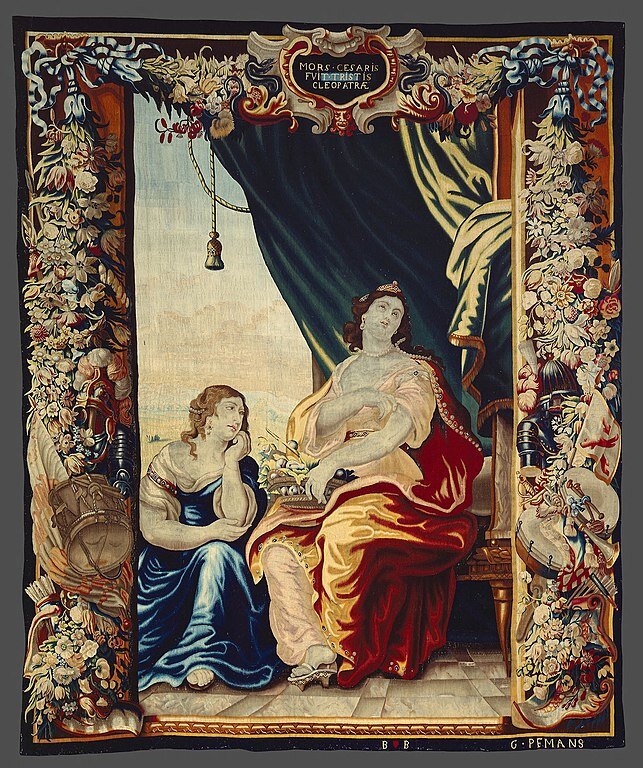

Cleopatra (69 — 30 BCE), the legendary queen of Egypt from 51 to 30 BCE, is often best known for her dramatic suicide, allegedly from the fatal bite of a poisonous snake. Here, Edmonia Lewis portrayed Cleopatra in the moment after her death, wearing her royal attire, in majestic repose on a throne. The identical sphinx heads flanking the throne represent the twins she bore with Roman general Marc Antony, while the hieroglyphics on the side have no meaning. Lewis was working at a time when Neoclassicism was a popular artistic style that favored classical, Biblical, or literary themes—thus Cleopatra was a common subject. Unlike her contemporaries who often depicted an idealized Cleopatra merely contemplating suicide, Lewis showed the queen’s death more realistically, after the asp’s venom had taken hold—an attribute viewed as “ghastly” and “absolutely repellant” in its day (William J. Clark, Great American Sculpture, 1878). Despite this, the piece was first exhibited to great acclaim at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and critics raved that it was the most impressive American sculpture in the show. Not long after its debut, however, Death of Cleopatra was presumed lost for almost a century—appearing at a Chicago saloon, marking a horse’s grave at a suburban racetrack, and eventually reappearing at a salvage yard in the 1980s. The Museum has an online exhibit that documents the statue’s storied history and conservation.

John Sartain, 1885, Engraving depicting Caesar Augustus' now lost painting of Cleopatra VII in encaustic, which was discovered at Emperor Hadrian's Villa (near Tivoli, Italy) in 1818. She is seen here wearing the golden radiant crown of the Ptolemaic rulers (Sartain, 1885, pp. 41, 44) and being bitten by an asp in an act of suicide. She also wears the knot of Isis (i.e. tyet) around her neck, which corresponds to Plutarch's description of her wearing the robes of the Egyptian goddess Isis (Plutarch's Lives, translated by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1920, p. 9.)

Statue of queen Cleopatra VII. Basalt, second half of the first century BC. Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Egypt, 2nd century A.D., Los Angeles County Museum of Art, image via Wikimedia Commons courtesy of LACMA

detail from the Tomb of Francis II, Duke of Brittany and his wives, Cathedral of Sts. Peter and Paul, Nantes, France

detail from Cassone made for Lorenzo Morelli, portrait attributed to Domenico de Zanobi, Courtauld Gallery

photo from Art Mirrors Art

Andrea della Robbia, Italian, c. 1475, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1921

Judy Chicago, Snake Goddess Place Setting (from The Dinner Party), 1979; Mixed media; Collection of Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; Photo courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts; © Judy Chicago

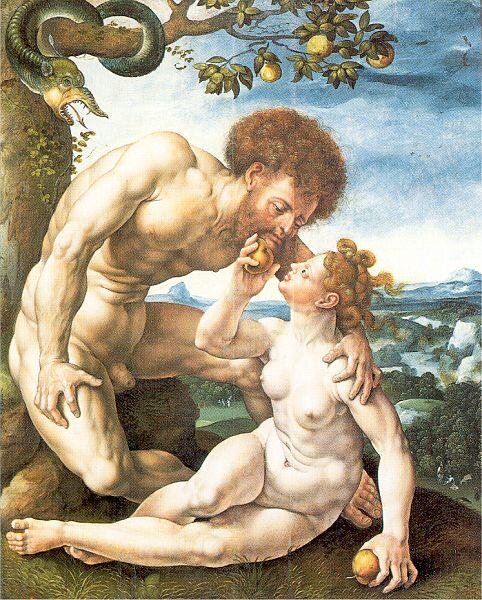

Jacob Jordaens, 1653, Baroque: Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

Artemisia Gentileschi, c.1620, Private collection Cavallini-Sgarbi Foundation, Ferrara, Italy

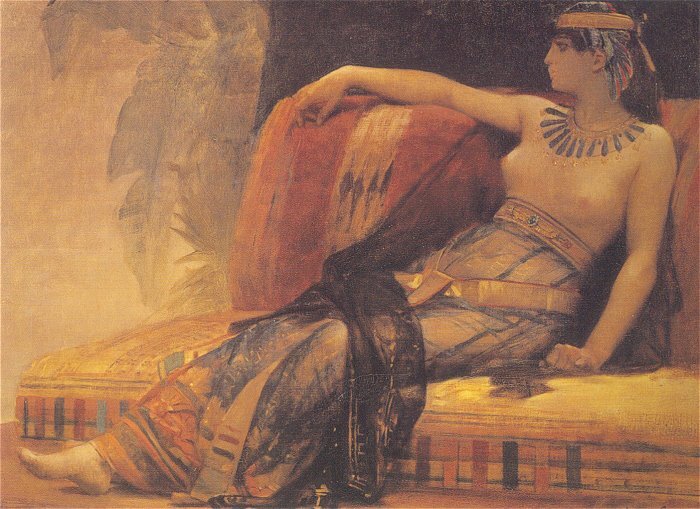

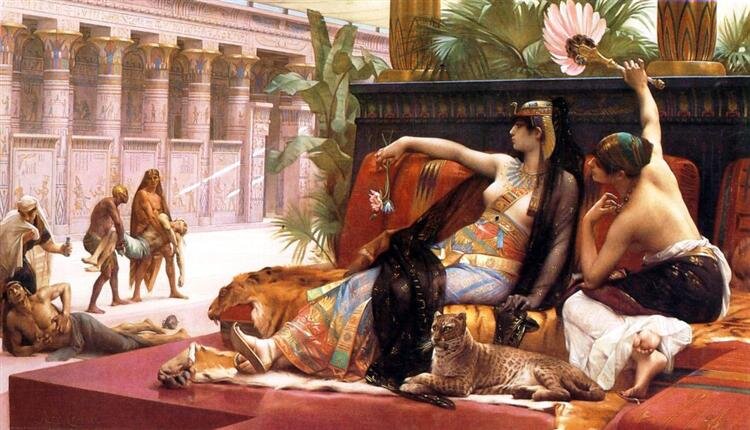

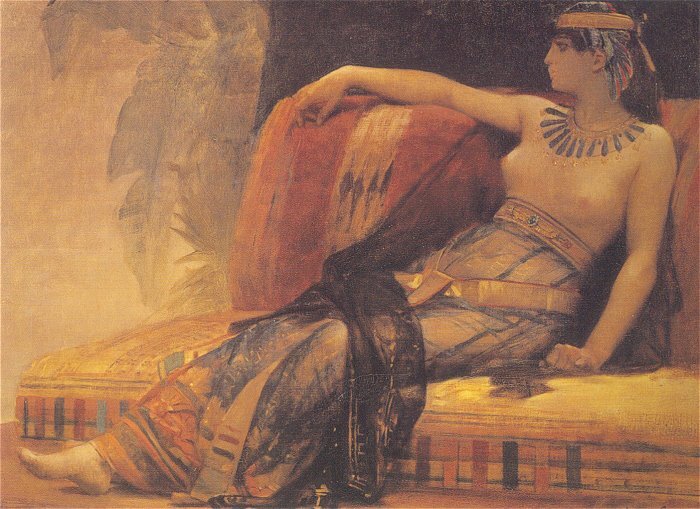

Alexandre Cabanel, 1887, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, Belgium

Alexandre Cabanel, Academicism